At the break of dawn last week, the 36-year-old Teyba Jemal lined up in front of Sheger Bread Shop in the Lafto neighbourhood. Dozen of others were waiting their turn in a queue. Teyba's palms were ashy from the early cold, and her eyes turned moist red, revealing that she had had little sleep.

Teyba had to wake up early. Not doing would see her two children, niece and husband leave home with empty stomachs. Bread is not a breakfast option at Teyba's house. It is a means of survival. The money she makes as a maid is insufficient to cover the 2,000 Br rent and buy her family Teff flour for the household. Its product, Injera, would cost 15 Br a piece in the retail market, leaving her to buy 20 bread loaves, each for 2.30 Br.

The bread distributors from Sheger Bakery have set a quota. The most a person can buy at once is 20.

"Either I buy this or not eat," Teyba told Fortune.

The queue grew by the minute. But the distributor, Adamu Mulat, was nowhere in sight. After 20 minutes, he arrived to confront what seemed like an orderly waiting line turned to chaos — Teyba and others began pushing each other aggressively. In his late 20s, Adamu had to show a long stick and urged his customers to behave.

"I don't blame them," Adamu told Fortune. "The bread is not enough for all."

A civil engineering graduate, Adamu partnered up with four friends and started distributing Sheger Bread a while ago.

With an investment of 900 million Br by Horizon Plantation, a subsidiary of MIDROC Ethiopia Group, the industrial-scale bakery in Akaki Qality District has a daily capacity of producing 1.6 million loaves of bread daily for a population of a city estimated to exceed four million. A loaf of bread from Sheger Bakery reached Adamu at two Birr, with a 30 cents margin to buyers but three times lower than what other bakeries sell.

Sourcing flour from farms under Horizon and cooperatives, the bakery, however, supplies over 400 outlets, such as those run by Adamu at half its capacity.

The long queue last week at Adamu's outlet resulted from the closure of two nearby shops. Buyers were anxious not to leave empty-handed; the shop received 1,000 pieces of bread during low days; this may increase to 2,500 pieces on a good day.

"It all depends on the supply," Adamu told Fortune.

The burden to produce a sufficient amount falls on food and flour factories facing a scarcity of wheat supply. Several flour mills face escalating wheat prices; a quintal of flour has skyrocketed from 600 Br to 4,000 Br in four years. Despite soaring prices, the unavailability of wheat push millers either to close or downsize their operations drastically.

One of the over 400 millers is Mizan Flour & Biscuit Factory, incorporated eight years ago.

It demands 400qtl of wheat daily to produce flour. However, Hussien Ahmed, the significant shareholder, was in despair about the meagre wheat supply that has led the factory to operate at 20pc of capacity. He had to let go of seven of his 47 employees while the remaining continued to work, albeit on and off.

The company, near the Lafto area, received half its demand for wheat three months ago but has been experiencing severe shortages since. Hussien and his managers had to source wheat with the help of intermediaries, paying an additional price of up to 5,000 Br. They sell a quintal of flour to bakeries for 6,500 Br at the factory gate.

"Consumers shoulder the burden," Hussien told Fortune.

The tribulations of Mizan are what many of the millers organised under the Ethiopian Millers' Association have been experiencing. Under Muluneh Lema, the millers saw their operations below capacity, struggling to remain in business as they no longer received 10 million quintals of wheat from the state at subsidised rates two years ago. Lobbying for over 200 flour mills for over 25 years, the Association's leaders tried to commission a survey of the millers; many declined to participate for fear of consequences, according to Muluneh.

"The scarcity is not recent," he told Fortune.

Hardly any of the millers under the Association have received wheat supplies for nearly two months. Managers of the state parastatals working in the industry agree.

The Ethiopian Industrial Inputs Development Enterprise's (EIIDE) last wheat procurement of 5,000qtl was in November 2022. Endeshaw Legesse, director of procurement, attributed the challenges to farmers' unions directly supplying the government and cutting the cord of the distribution chain.

Federal and regional authorities are hard-pressed to realise the ambition of making Ethiopia a net wheat exporter. They are toiling with the hope of meeting the highly publicised pledge of making the country earn hundreds of millions of dollars from buyers in neighbouring countries. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) and the head of the Oromia Regional State, Shimelis Abdisa, announced two weeks ago the first batch of 1.2 million quintals harvested in the Bale Zone.

The Oromia Regional State aspires to take the largest share, covering 100 million quintals of the estimated 164 million wheat production expected to be harvested through the Meher, Belg and Bega seasons. Its officials claim to have 2.8 million hectares of land cultivated in the region.

However, these are numbers inconsistent with data from international organisations monitoring global wheat production and marketing.

A study commissioned by the USAID Ethiopia office to survey the wheat market for last year concluded that Ethiopia would be unlikely to achieve a seven million tonnes harvest in five years. The study says Ethiopian farmers will find it difficult to plough over 2.1 million hectares of land. Another report by the Foreign Agricultural Services Bureau of the US Department of Agriculture has projected Ethiopia's wheat production for the current year at 5.5 million tonnes, a volume three times lower than what Ethiopian agriculture authorities wanted to see.

Despite these differences in projections, the Oromia Regional State authorities continue to aspire to ensure 15 million quintals of wheat are shipped to East African markets such as Kenya, Djibouti, and Somalia.

Farmers in some zones do not appear pleased with the plan as they prefer to sell wheat in the domestic market, fetching better prices.

Mohammed Amanalo, 37, a farmer in the Bale zone, grows wheat twice a year in Kiremt and Belg seasons. The skyrocketing production costs for inputs such as fertiliser, chemicals and pesticides have been a constant headache for him, pushing his expenditure for three hectares to 90,000 Br.

Mohammed harvested 600Qtl wheat from the nine hectares plot he ploughed during the Kiremt season, including the four-hectare he rented from a neighbour for 130,000 Br for three years. Leaving some for household consumption, he sold the 420Qtl wheat for 3,200 Br a quintal under the pressure of the local authorities.

"We can't say no to the government," Mohammed told Fortune.

Complaints are rising a few kilometres outside the capital as well. A farmer near Bishoftu (DebreZeit) town, Oromia Regional State, Alemu Tesema, 50, has been farming all his life. A sole breadwinner for his wife and two children, Alemu is one of tens of thousands of farmers in the region persuaded to join a cluster farming program, a federal government initiative aiming to boost agricultural productivity.

Alemu merged two hectares of land with eight of his peers: he saw up to 20Qtl spike during the Kiremt season production.

However, he was discontented with the regional bureau selling price officials set at 3,200 Br for a quintal. According to Alemu, the price fails to consider the production costs, such as pesticides and labour put in during harvest. During several meetings with local authorities, farmers' complaints have fallen on deaf ears as the price cap stood firm beginning last year.

"No one wants to get less than what they spent," he told Fortune.

The market offers 1,300 Br more.

Beriso Feyisa, deputy head of the Oromia Agriculture Bureau, claims the farmgate price exceeds production costs, describing the margin for farmers as "reasonable." Crediting the Bureau for supplying agricultural inputs with loans, he disclosed the current export generating 50 dollars from quantal (2,685 Br at last week's exchange rate), revealing a 700 Br loss from the farmgate price.

"The forex would be used to buy agricultural inputs," he told Fortune.

The Ministry of Trade & Regional Integration and the Ethiopian Trading Businesses Corporation, a portfolio company of the Ethiopian Investment Holdings, are the gateways to the ambitious export plan. Their officials have declined to comment on this story.

For an economy starved of foreign exchange, every dollar to the central bank's coffer means a lot to the authorities. Minister of Finance Ahmed Shide hoped to see the country generate 200 million dollars from its first export. But this represents less than a quarter of what is spent on buying fertilisers in the fourth quarter of 2022. In the fourth quarter, the cost of fertiliser imports surged by 229pc, to 870 million dollars.

The World Bank estimated Ethiopia's average fertiliser use at over 36Kgs per hectare. The price of a quintal of fertiliser had shot up by as much as 80pc last year following Russia's war in Ukraine.

Ethiopia's annual demand for wheat increased by 25 million quintals this year, reaching 97 million, excluding the need for humanitarian assistance. The civil war in the north has played a significant role in increasing the number of internally displaced people needing food aid. World Food Program (WFP) reveals that more than 20 million people require food assistance, of which 7.9 million are under productive safety net programs.

However, officials are offering aid organisations to buy wheat from the domestic "surplus" with foreign currency, thereby putting pressure on the domestic market.

"They can source it from the local market," said Esayas Lemma, head of the drop development directorate under the Ministry of Agriculture.

A change in lifestyle and urbanisation is attributed as the cause for the boost in demand, according to Esayas. He said most farmers consume 60pc of what they produce during the Meher season.

While applauding the efforts to become self-sufficient in wheat, experts question the wisdom of exporting wheat before ensuring local demands are fully covered. Adane Tufa, an agricultural economist, is one of these experts who believe the market reflects the gap in the wheat supply chain.

A macroeconomist requesting anonymity said that export should not be a priority in a country where inflation has diminished household incomes. He argued the country would not be competitive in the international market without lowering its price. Top wheat-exporting countries like Ukraine compete in the global market with lower prices as they do not import agricultural inputs like fertiliser.

Agricultural exporters have used the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) trading floors, including over 20 commodities, for over 14 years to source and ship grains to overseas markets. Wheat was added to the floor last October; the trading has yet to start.

According to Netsanet Tesfaye, corporate communications manager, the plan forwarded by the federal and regional authorities to export wheat to neighbouring markets is separate from the ECX.

The authorities may push the narrative of Ethiopia as net wheat exporters as many wonders with uncertainty and pundits continue to question the wisdom of sending the grain away while the domestic market is starved. Teyba felt lucky that early morning for buying all the 20 loaves. Adamu had brought more bread than usual, a pleasant surprise he doubted could be repeated often.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 18,2023 [ VOL

23 , NO

1190]

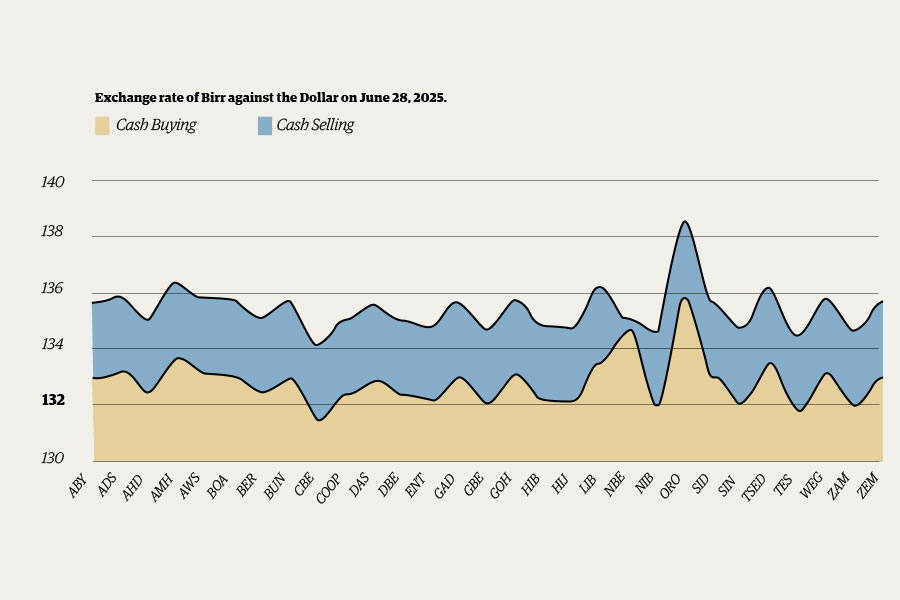

Money Market Watch | Jul 06,2025

Fortune News | Nov 09,2024

Fortune News | Aug 11,2024

Verbatim | Aug 13,2022

Radar | May 23,2021

Verbatim | Nov 12,2022

Editorial | Dec 30,2023

View From Arada | Apr 27,2024

Radar | Jul 17,2022

Fortune News | Jun 14,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Jul 12 , 2025

Political leaders and their policy advisors often promise great leaps forward, yet th...

Jul 5 , 2025

Six years ago, Ethiopia was the darling of international liberal commentators. A year...

Jun 28 , 2025

Meseret Damtie, the assertive auditor general, has never been shy about naming names...

Jun 21 , 2025

A well-worn adage says, “Budget is not destiny, but it is direction.” Examining t...