Sep 27 , 2025.

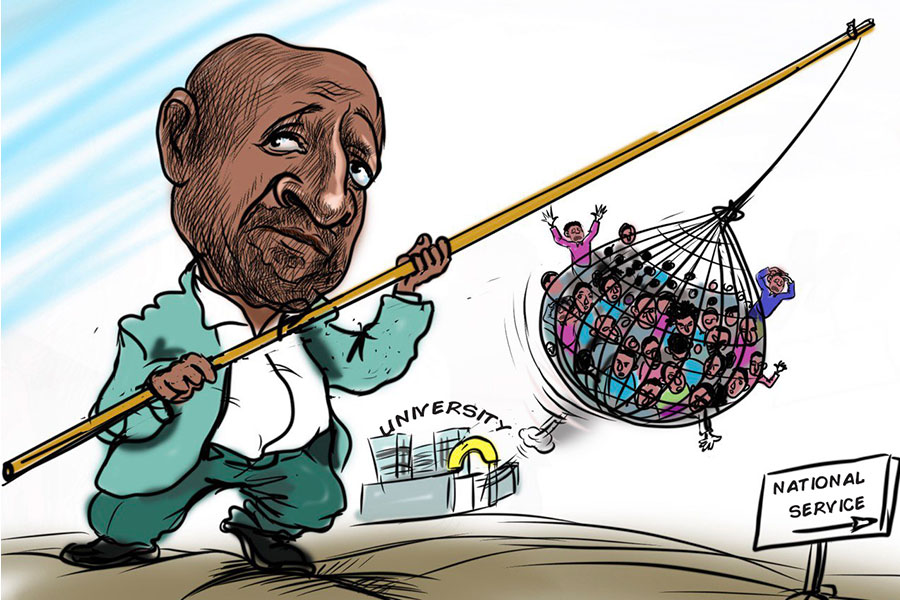

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national mood has shifted from hope to a more sobering reckoning. The administration's radical new approach to secondary-school exams, conceived as a cure for systemic rot, has laid bare the depth of the crisis. Education authorities have adopted a drastic measure to address cheating in the school system. Since 2021, every secondary-school candidate has been transported to a university campus, sometimes kilometres from home, to sit national exams watched by unfamiliar invigilators and unblinking cameras.

The scheme, driven by Berhanu Nega, a professor-turned-education minister, seeks to sever the cosy ties among students, teachers and local officials that allowed answer sheets to circulate like currency. In a country where a paper qualification is still seen as a ticket out of poverty, stamping out cheating promised to restore faith in merit and signal that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s Administration will not tolerate the skulduggery that once made national results a national joke.

The decay that inspired such theatre was real. Years of leaked papers, whispered bribes, and lax marking had drained the meaning from exam scores. Universities complained of first-year students who struggled to write a coherent paragraph. Ask any employer, and they would affirm that degrees have become worthless. Education policymakers concluded that only shock therapy could rebuild trust. Their prescription is brutal and messy, yet unavoidable. They had hoped that computer screens, sealed envelopes and remote venues would make dishonesty not merely risky but futile.

Four exam cycles later, the treatment has exposed the illness more shockingly than ever. Nearly three million pupils have sat the re-engineered tests. Fewer than one in 10 managed to score above 50pc. During the 2024 sitting, 42.8pc of the 3,106 schools that entered candidates produced no pass, while thousands of other schools saw every hopeful fail. Berhanu and his team have moved the goalposts only to discover how few strikers they have possessed.

This year, about 95pc of candidates fell short of the threshold for a state-funded place, shattering the ladder that many families had counted on to climb into the middle class. Among the 134,000 students who took the new online papers, lauded for preventing leaks and enabling instant marking, only 21.7pc squeaked through. What was meant to defend merit now reveals a harsher truth of an education system that is unable to impart the knowledge that merit requires.

Anyone who visits a typical public school sees the reasons. For decades, officials prioritised enrollment over achievement; classrooms are packed, textbooks scarce, and buildings are cracked. Lessons rely on rote learning, which is useful for recalling answers, but hopeless for grasping a concept. Head-teachers, pressed to show progress, long ago embraced generous grading. Parents mistook flattering report cards for genuine learning until the new exams exposed their children’s frailties.

The deficits start early and widen. Fewer than two-thirds of the 35.4 million school-aged youngsters are enrolled. Close to 12.5 million receive no schooling whatsoever due to conflict and displacement. Conflict-hit regional states keep almost half their children at home. National surveys find that nine in 10 ten-year-olds cannot read a simple sentence. Electricity, desks and even chalk are luxuries in thousands of classrooms.

A cleaner exam cannot brighten a room lit only by a cracked window and staffed by an under-qualified teacher.

Inequality, once muffled by inflated grades, now glares under the harsh light of "honest" marking. Boarding schools flush with resources boast pass rates of 71pc, while well-funded community institutions manage 51pc. Most public schools, urban and rural alike, floundered. Even two-thirds of candidates from private academies failed the latest exam, showing that fees cannot paper over systemic weakness. For rural students, the ordeal begins before dawn, with hours on dusty roads, borrowed bus fare and a night on a stranger’s dormitory floor before a test that will likely dash their hopes.

Supporters of the crackdown insist that discomfort is precisely the point. By exposing the ugly truth, they say, the policy forces schools to change. The Education Minister cites “encouraging trends”, noting that the share of genuinely earned scores is creeping up, even if the absolute numbers remain grim. His Ministry predicts that teachers will adjust their methods, students will raise their effort, and pass rates will climb.

Targets have been set. Within three years, 15pc to 20pc of candidates should succeed. That is a low bar, but still a steep climb from today.

Critics retort that Berhanu and his ilk have confused policing with pedagogy. Laboratories, libraries, and support centres promised in glossy policy blueprints remain dreams. Efforts to equip schools with practical equipment have stalled due to limited budgets and bureaucratic hurdles. Teacher training lags behind the standards officials demand. Many instructors lack advanced degrees or regular refresher courses. Yet students face uncompromising scrutiny. The result, sceptics warn, is a punitive classroom that judges children for failings rooted far upstream.

Digitisation was meant to guarantee probity; instead, it often magnifies hardship. Teenagers take high-stakes tests on unfamiliar tablets in halls where electricity or internet access is unreliable. Servers crash, power cuts strike, and screens freeze while the countdown clock ticks. Rural families scrape together travel money only to confront logistical chaos and, by many accounts, indifferent invigilators. Stress piles atop the disadvantage already baked into years of threadbare schooling.

The mismatch between what schools teach and what employers need is widening. The curriculum leans heavily on theory, while practical skills, vocational, and digital literacy lag quite behind. Youth unemployment is high, the formal industry meagre and farm life increasingly unappealing. Graduates emerge over-examined and under-prepared, funnelling into informal jobs or migrating abroad. A tamper-proof exam cannot conjure opportunity when the wider economy offers little.

However, education officials insist their shock therapy will pay dividends. They speak of harnessing exam data to target resources, tethering teacher promotions to pupil outcomes and corralling donors to build the missing labs. Yet the treasury’s coffers are thin, and parents’ patience is thinner still. Teachers need salaries that keep them in classrooms, not encourage them to moonlight. Schools need stocked libraries, working science kits and reliable power, not official slogans.

The past three years have shown that honesty, though indispensable, is not enough. Without good teaching, sound materials and decent facilities, control becomes a mere spectacle and slams yet another door in the face of aspiration. The danger is not only the loss of a cohort. It is the creeping doubt that schooling can deliver progress at all, a risk no country, least of all one as youthful and ambitious as Ethiopia, can afford.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 27,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1326]

Fortune News | Feb 09,2019

Viewpoints | Jul 17,2022

Commentaries | Apr 26,2025

Fortune News | Apr 19,2025

Commentaries | Feb 13,2021

Commentaries | Sep 07,2019

Editorial | Apr 13, 2025

Commentaries | May 13,2023

Fortune News | May 27,2023

Fortune News | Sep 26,2021

Photo Gallery | 170892 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 161131 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 150798 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136266 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In Meqelle, a name long associated with industrial grit and regional pride is undergo...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is set to roll out a new "motor vehicle circulation tax" in th...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The Bank of Abyssinia is wrestling with the loss of a prime plot of land once leased...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The Customs Commission has introduced new tariffs on a wide range of imported goods i...