Commentaries | Nov 11,2023

Feb 23 , 2019

By Meaza Ashenafi

Reforms have been taken in the justice system, but more efforts are necessary to restore public confidence in the judiciary, writes Chief Justice Meaza Ashenafi, president of the Federal Supreme Court.

Following political transformation in Ethiopia over the last 10 months, the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) took a courageous and unprecedented step to ensure gender parity in key leadership positions. The appointment of women as head of state and president of the Federal Supreme Court is indeed unprecedented.

Likewise, gender parity, where women hold half of the ministerial cabinet positions, has become an inspiration not only in Africa but on the global stage as well. The careful selection and appointment of key female leaders demonstrate the administration’s desire to respond to the aspiration of the public. Citizens demand independent and strong development, democratic, justice and security institutions that have been lacking in our country.

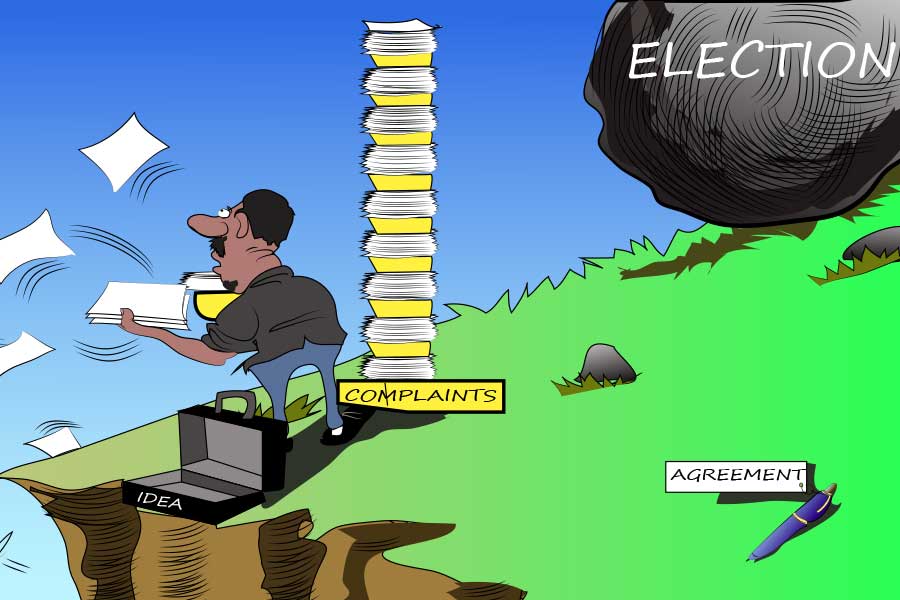

Indeed, since last year, reforms in Ethiopia have started in earnest. On the justice front, amnesty has been granted to thousands of prisoners; draconian laws imposed on civil society organisations have been amended, and revisions in electoral and media laws are underway.

The crucial, overarching mission at this time is restoring public confidence in the judiciary, a matter I stressed when elected as Chief Justice last November.

Since then, we have embarked on engaging stakeholders in our judicial system, an uncommon practice in our country. We have held town hall meetings with 350 Federal Court judges, 3,500 professional and support staff of the Federal Court, 400 practising lawyers and presidents of regional supreme courts from across the country. Key concerns and issues were addressed during these town hall meetings. We assessed the damage done to the rule of law and expressed our collective aspiration for the supremacy of the law and the independence of the judiciary.

It was an opportunity to communicate to our judges that their mandate is to abide by the rule of law, conduct fair trials, observe due processes, uphold the equality of every citizen before the law, and stand for the impartiality of the administration of justice.

We are already observing the positive impacts of this shared commitment. A high-powered Judicial Reform Advisory Council composed of former judges, senior lawyers and academics has been established.

Our reform agenda includes the revision of our court structures and the redesign of the judicial administration system, including composition and mandate of the Judicial Council and procedures for the appointment and removal of judges. We are also addressing cross-cutting issues that affect judicial independence and service delivery. We are strengthening the existing alternative dispute resolution mechanisms and setting up new ones as we consider these measures to be vital in managing the overflow of cases in our formal court structures.

To implement reforms successfully, we rely on international principles and standards as well as “good fit” practices. To do that, we are forging alliances with international partners such as the UNDP, USAID, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and the Open Society Foundation. More partners have shown interest to support our reform agenda.

The engagement of stakeholders and outreach activities and the creation of more platforms for awareness and understanding is crucial. We need space to invite stakeholders and change-makers from the judiciary, bar associations and governments.

Given the complexity, the multiple inputs required and the diversity of expectations on the judiciary, we need to increase the number of innovators and change makers who are addressing the issues of law and justice.

Citizens must and can initiate change and pressure officials of the judiciary. But change also ought to be a two-way street, and members of the judiciary should be able to meet the public half way. It will mean staffing the judiciary with independent-minded judges, a matter that entails a unique vetting process.

Judicial vetting often applies in the appointment of new judges. However, judicial vetting has also been applied to sitting judges in some countries with a view to restoring public confidence, especially in the context of political transition.

The experience of former communist eastern European countries is noted here. In East Africa, Kenya is well known for vetting sitting judges - first after the adoption of a new constitution in 2010 and later in 2013, when a new Chief Justice implemented the “Radical Surgery”. The procedure though has been questioned for its impartiality and the disruption caused on judicial functions.

In the case of Ethiopia, we have opted to take a less radical approach. Some judges left on their own accord, but most remain in office and continue normal functions. Our approach involves finding the right balance to avoid legal complications, disruption of the much needed judicial services and screening of judges who are corrupt and grossly incompetent.

In view of these, we are collecting informal feedback from judicial leaders, peer coordinators and lawyers about the competence and integrity of individual judges.

Questionnaires are also being administered to collect the views of litigants, and we are also reviewing existing disciplinary complaints against judges. While systematic inspection of files is underway, the collection of data on unjustified assets will be launched soon. Such evidence will be analysed objectively and qualitatively based on a transparent process.

New approaches are being utilised in order to prevent future vetting of sitting judges. We need to make concrete efforts to attract good judges based on competence and integrity and make a clean break from recruiting judges based on political loyalty that defeats the purpose of judicial independence.

This means having to address the issue of salaries and benefits. Justice is not cheap, and Ethiopia, as one of the lowest paying countries, needs to address this challenge progressively and incrementally.

The judiciary should also be a learning organisation, and training opportunities should be available. Just as critical is to revise our appeal procedures and to implement alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. This way, we can reduce the workload on judges and recruit and retain a reasonable number that can provide quality judicial service.

Subsequently, it is important to reinforce existing soft laws such as the “Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary” and the “Bangalore Principle of Judicial Conduct.”

Such principles require further elaboration and affirmation. There is a need to pluralise and adopt the principles in our day to day work. Indicators related to the rule of law and judicial independence should feature as a critical area of accountability for national, regional and international monitory and peer review mechanisms.

This is all with the view that the rule of law and trust are crucial to enable people who do not know each other personally to live together in harmony.

A society that is unstable and has low levels of trust is caused by the lack of faith in a fair and swift judicial system. If citizens have no faith in the judiciary, they will have no trust in government in general.

“All the rights secured to citizens under the constitution are a mere bubble, except guaranteed to them by an independent judiciary,” as Andrew Jackson, seventh president of the United States, said.

PUBLISHED ON

Feb 23,2019 [ VOL

19 , NO

982]

Commentaries | Nov 11,2023

Editorial | Nov 29,2020

Editorial | Apr 27,2024

Editorial | Jul 20,2019

Commentaries | Jun 21,2025

Life Matters | Dec 17,2022

Radar | Aug 23,2025

Commentaries | Apr 04,2020

Commentaries | Mar 07,2020

Sunday with Eden | May 01,2020

Photo Gallery | 170378 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 160615 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 150250 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 136246 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

In Meqelle, a name long associated with industrial grit and regional pride is undergo...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The federal government is set to roll out a new "motor vehicle circulation tax" in th...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By NAHOM AYELE

The Bank of Abyssinia is wrestling with the loss of a prime plot of land once leased...

Oct 5 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

The Customs Commission has introduced new tariffs on a wide range of imported goods i...