When the central bank imposed a freeze on collateral-based loans last August, there was no shortage of outcries from businesses across industries and sectors. The freeze was lifted at the end of November, but many are reeling from its consequences.

Yordanos Assemire is among the businesspeople awaiting the approval of a loan she had applied for in the weeks leading up to the freeze. She waited patiently until regulators rescinded the suspension, hoping to get 16 million Br in credit from one of the private commercial banks. An exporter of seeds and an importer of furniture, Yordanos had no trouble having credit approved in the past. The approval process for a loan of a similar amount would have taken the banks no more than a month in her experience.

It has been around six months since she has applied now.

The wait has left her business halted. Yet, she has to service a 9.4 million Br debt previously taken from another commercial bank.

"We're just paying interest," she said. "I could at least set off the payment with the new credit."

The application would be approved by the end of last month, officers at the bank where she applied told her. Yordanos has visited a few other banks to weigh her options, but the effort was in vain. When businesses are short of operating cash, they tend to borrow from one another. However, many businesses are in the same dire situation.

Yordanos' experience and that of many others in business is a telltale sign of a liquidity crisis in the banking industry. Regulators at the central bank had their eyes on restraining what they saw as "unhealthy" loan provisions when they imposed the loan freeze.

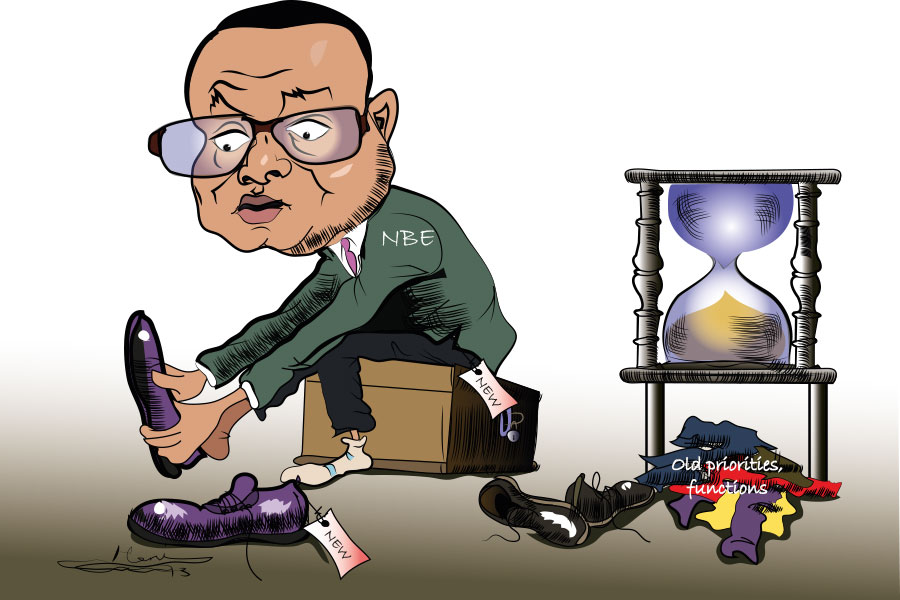

The month before the freeze was imposed in the fourth quarter of 2020/21, banks disbursed over 105 billion Br in loans. The state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) accounted for 40pc, showing a 66pc year-to-year increase. They had disbursed close to 330 billion Br last year. The month of July alone saw outstanding credit grow by 125pc compared to the same period the previous year. This alarmed the authorities at the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE), leading the board under Girma Birru to take the unusual decision of a blanket loan freeze.

"The NBE board . . . stands ready to utilise all available policy tools at its disposal to ensure price and financial stability consistent with its legal mandate," read a statement issued by the central bank in September last year.

The authorities gradually relaxed restrictions to exempt importers, coffee exporters, edible oil producers and petroleum companies.

The measure seems to have met its intended purpose as banks' outstanding credit has shown a marginal increase since. At Awash Bank, with the biggest share among the private banks, loans grew by about two billion Birr over the first quarter, five times lower than the average quarterly growth observed in the preceding year. The Bank of Abyssinia, the second-largest private creditor, disbursed 2.4 billion Br in the first quarter. It had disbursed close to 40 billion Br last year, the highest among private banks.

"Loan provision takes up the highest share in deposit mobilisation," said Melaku Kebede, president of Hibret Bank.

Loan provisions in the first quarter may seem smaller compared to past performances. But they still represent a significant amount considering the decline in deposit mobilisation apparent across the industry. Only six of the 17 private banks attained positive deposit mobilisation over the first quarter. Coupled with sluggish loan repayment collection, the banking industry appears to be heading to a liquidity crunch. The industrial average for loan-to-deposit ratio (LDR) reached 82pc in June last year, growing by two percentage points over the first quarter.

The loan-to-deposit ratio serves as one of the essential indicators to measure the banking industry's health. Chris Murphy, an editor and financial writer for more than 15 years covering banking and the financial markets, sees the ratio as a measure of how well a bank is managed.

"If the bank isn't increasing its deposits or its deposits are shrinking, [it] will have less money to lend," says Murphy, writing for Investopedia. "In some cases, banks borrow money to satisfy loan demand in an attempt to boost interest income. However, if a bank uses debt to finance its lending operations instead of deposits, the bank will have debt servicing costs since it will need to pay interest on the debt."

Neither is having a low deposit-to loan ratio a measure of a bank well run. It shows it is not lending, affecting its income from interest, a significant source of revenue for the banks, often comprising over two-thirds of income. Thus, striking a good balance, experts advise not to exceed 90pc.

"The proper LDR is a delicate balance for banks," says Murphy. "If banks lend too much of their deposits, they might overextend themselves, particularly in an economic downturn. However, if banks lend too few of their deposits, they might have opportunity costs since their deposits would be sitting on their balance sheets, earning no revenue. Banks with low LTD ratios might have lower interest income resulting in lower earnings."

Almost all the banks have seen their loan-to-deposit ratios stagnate, if not eroded. Debub Global Bank leads the pack with the highest ratio at 97pc by the end of September last year, followed by Lion Bank at 91pc. Neither have the big banks with a quarter-century of experience under their belts been spared. With the sharpest decline in deposit mobilisation in the industry, Dashen Bank carried through the quarter with a 90pc ratio. Its close contender, Awash sustains 87pc, followed by Abyssinia's 85pc and Hibret's 83pc.

For Abudlmenan Mohammed, a finance expert who has closely followed Ethiopia's financial sector for 20 years, a ratio beyond 80pc should be considered "unhealthy". He argues that when factored for reserves and payments and settlement accounts, the high ratios mean the banks are hungry for cash.

Several factors set off the slow deposit mobilisation in the industry. The loan freeze has reduced the money multiplier effect the banks used to enjoy.

For over a year now, the banks have had to deal with the war in the north, undermining their operation in collecting deposits from the areas active in the conflict. More than 600 bank branches in the Tigray Regional State remain out of business. The experience of Wegagen Bank is particularly illustrative.

About one-third of Wegagen branches are located in Tigray Regional State, an area outside the reach of its operations since June last year. Wegagen had collected a little over 1.4 billion Br in deposits last year, much lower than the industry average and a hundred times less than the state-owned CBE.

The war has significantly affected deposit mobilisation, according to Afework Gebretsadik, director of marketing at Wegagen.

Deposit mobilisation was not the only one affected by the ongoing armed conflict in the north. Loan recovery was halted. Banks have been unable to recoup credit disbursed to clients in areas affected by the war. Non-performing loans (NPLs) have surged as a result.

Wegagen Bank saw a 410pc leap in loan impairment charges last year.

There are other factors behind the impending liquidity crisis. A policy shift by the central bank has caused an acute strain on banks. It has instructed banks to double the amount of their reserves from five percent of their deposits. This, too, was an attempt by regulators to tighten the rope on credit disbursement. They curtailed the private banks from injecting 65 billion Br into the market with such a decision.

The banking industry is far from consolidation. Cash moves around with the entry of new banks. The past few months have seen the establishment of Hijra and Goh Mortgage banks, which entered the industry with a combined paid-up capital of 1.2 billion Br. As other banks, including Amhara, Tsehay, Gadaa, Ahadu and Ramis, prepare to follow suit with a combined paid-up capital of 8.5 billion Br, the "industry will see a struggle," according to an executive of one of the private banks.

Even in ordinary times, deposit mobilisation is a daunting task, especially for private banks. The economic downturn, cash-hoarding, and low financial penetration in rural areas are common issues they face. The Birr notes outside the banking system reached 133 billion Br at the end of June last year, 24 billion Br more than the figure from the previous year.

This could have been due to the weekly transaction limit imposed a year ago, according to Dereje Zenebe, CEO of Zemen Bank. Central bank authorities lifted this restriction early last week.

"We'll see if this will have an impact," said Dereje, whose bank has a loan-to-deposit ratio of 73pc. "The priority for me is liquidity risk."

The inflationary pressure that clocked in at 33pc last month is fuelling the desire of depositors to take their money out. This puts pressure on the banks to avail more cash.

Although Melaku of Hibret Bank sees improvement since banks began providing loans, he says it is not the time to be off guard. He said banks would have to work harder on deposit mobilisation to avoid an industrywide crunch in liquidity.

A liquidity crunch is not new to the industry. One of the worst such crises was seen over two years ago when banks struggled to pay out withdrawals. Excessive lending and seasonal demands for cash were a frightening prospect only curtailed after the central bank lent 15 billion Br to bail out the industry. Almost all the banks had borrowed from the central bank for an interest rate double the amount they paid to their depositors.

The current problem is not as severe as it was then, according to Dereje of Zemen Bank. Several banks are managing on their own now, without borrowing from the central bank.

However, others rush to patch up the mess. Some banks have taken expensive loans from the central bank, agreeing to a 16pc interest rate. Others are scrambling to collect cash in fixed deposit accounts, which ordinarily offer higher interest rates than regular savings accounts. Some banks, such as Enat and Debub Global, have seen their fixed deposit to total deposit ratios rise to 42pc and 30pc, respectively.

Fixed deposits do not hurt the banks, according to Abdulmenan. But, it is expensive and affects their profitability.

The credit demand in the economy may not be within the capacity of the banks, according to Frezer Ayalew, director of banking supervision at the NBE. The central bank has stepped in allowing banks to lend coffee exporters two percent from their reserves until June this year. The reserves are to be paid back by August.

Frezer disclosed that allowing banks to dip into their reserves was made to address their plights.

The move is embraced by both the banking industry and coffee exporters. It coincides with the peak harvest season, which brings a rise in the need for working capital.

"I expect such well-timed policy measures from the central bank," said Melaku of Hibret Bank.

Abdulmenan contends the decision could benefit the banks but contradicts the central bank's policy in adjusting reserve requirements to ease inflationary pressure in the economy.

"It shouldn't be the central bank's priority to dictate which industries receive loans," he said.

Regulators at the central bank fall short of admitting a liquidity crisis shadowing the banking industry. They chose to see it as a common phenomenon observed at this time of the year.

"It's peak export season when issues are expected," says Solomon Desta, vice governor of financial institutions at the NBE.

The banks have complied with the central bank's liquidity requirements, Solomon told Fortune.

Central bank officials held a series of discussions with executives of commercial banks two weeks ago. The issues were dominated by concerns over foreign exchange crunches and the need to beef up deposits. Despite the tumult, bank executives seem upbeat about what the future holds, encouraged by the loans freeze lifted. They hope the provision of loans will stimulate the market, which will improve deposit mobilisation.

"I'm hopeful that the next half year will make up for the past one," Melaku told Fortune.

It is a level of sanguinity businesspeople such as Yordanos, who still await the approval of loan applications, want to see.

PUBLISHED ON

Jan 15,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1133]

Radar | Apr 08,2023

Fortune News | Dec 23,2023

Radar | May 09,2020

Radar | Nov 06,2021

Radar | Aug 05,2023

Radar | Dec 04,2022

Radar | Dec 29,2018

Editorial | Apr 24,2021

Fortune News | Oct 23,2018

Fortune News | May 28,2022

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 4 , 2025

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...

Sep 27 , 2025

Four years into an experiment with “shock therapy” in education, the national moo...

Sep 20 , 2025

Getachew Reda's return to the national stage was always going to stir attention. Once...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...