Commentaries | Feb 03,2024

A couple of months ago, I met an old colleague, a senior veteran army officer old enough to be my father. When we worked together, he used to be illustrious for his discipline and admired for his attention to detail. Unlike many of us, he also often used to talk about the elementary school he was from, while the rest of us were more interested in reminiscing about our college days.

He repeatedly mentioned the only formal school he went to, the names of the few friends he had in the classroom, and a range of anecdotes. When I met him once again many years later, it seemed even more strange he is still obsessed with, in his own words, the “good old days' elementary school.” He viewed it as a solid basis for the pieces of training he went through as he progressed from a private to a high ranking officer in his long career in the military. Many colleagues used to downplay his statements, arguing it was probably because he never managed to advance past elementary schools.

It was not, and I can testify. The first grade was a joy in our public school, despite all the changes and upsets we would undergo. The merrymaking and the student-led learning by the university students out for service would fade as they were taken over by the older dry-as-dust teachers. Still, we managed to make the best of it.

While in grade two, for some reason, I sat near the back of the row. Behind me sat three boys much older than me. All our teachers focused on them, as they were the most experienced and thus the best performing students in class. I stood fourth in the first semester exams behind the three older boys. Being happy with my result, our homeroom teacher moved me to the front row to inspire my age equals.

But as attention from the other teachers was still towards the three boys, and I was too far away from the necessary influence from them, my second-semester result was a disaster. Worse still, academic skills did not count for much among the new set of students I was forced into by the teachers. I needed to find a place among this new group – fighting to prove where I stood among my age band. Most of the new gang were from Filwuha, on present-day Yohanis Street, a neighbourhood notorious for gang spirits.

As peer pressure mounted, thus did concern from my parents about my falling grades. My dad enrolled me at Prince Sahleselassie School for summer. The same day after lunch, I started walking to my new private school, shaking with rage, as though I had a tormenting pain in the neck. The new school’s crumbling façade, even worse than a public school, added to the headache.

It took me only a week to learn that schools are never only buildings. It was a teacher, whose first name was Dhabaa, which completely changed me, not through cracking whips but the fatherly smile-laden attention he afforded to the eight of us who made up his classroom. The shortest yet meaningful two months came to an end, and it was with tears. I had to return to my public school. My family never budged to my repeated plea to continue at Prince Sahleselassie school.

The road to the school remained my favourite walking route as I walked alone or with my friends, until it was nationalised and merged with another school, and the compound was changed to a kebeleoffice. Passing by the school was a way for me to salute my teacher, who taught us much about personal hygiene, discipline, group work and the importance of academic pursuits, all the while remaining playful.

I hope the same prevails today. Initiatives such as school-feeding programmes are commendable, as is the expansion of schools and facilities to reach more children. But there also needs to be much investment in teachers. Elementary schools make or break the long-term outcome of kids. Few manage to survive a bad experience at that level and turn it around in their adulthood.

If we take care of the entrants at elementary levels, where it matters most, focusing the essence of learning on the right balance between teacher- and student-led, it would be a significant step in bolstering the school system and beefing up Ethiopia’s human capital.

PUBLISHED ON

Aug 28,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1113]

Commentaries | Feb 03,2024

Sunday with Eden | Mar 13,2021

Viewpoints | Jul 31,2021

Editorial | Jul 30,2022

View From Arada | May 23,2021

Fortune News | Apr 25,2020

Agenda | May 20,2023

View From Arada | Oct 09,2021

Sunday with Eden | Feb 08,2020

Fortune News | Mar 16,2020

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Oct 25 , 2025

The regulatory machinery is on overdrive. In only two years, no fewer than 35 new pro...

Oct 18 , 2025

The political establishment, notably the ruling party and its top brass, has become p...

Oct 11 , 2025

Ladislas Farago, a roving Associated Press (AP) correspondent, arrived in Ethiopia in...

Oct 4 , 2025

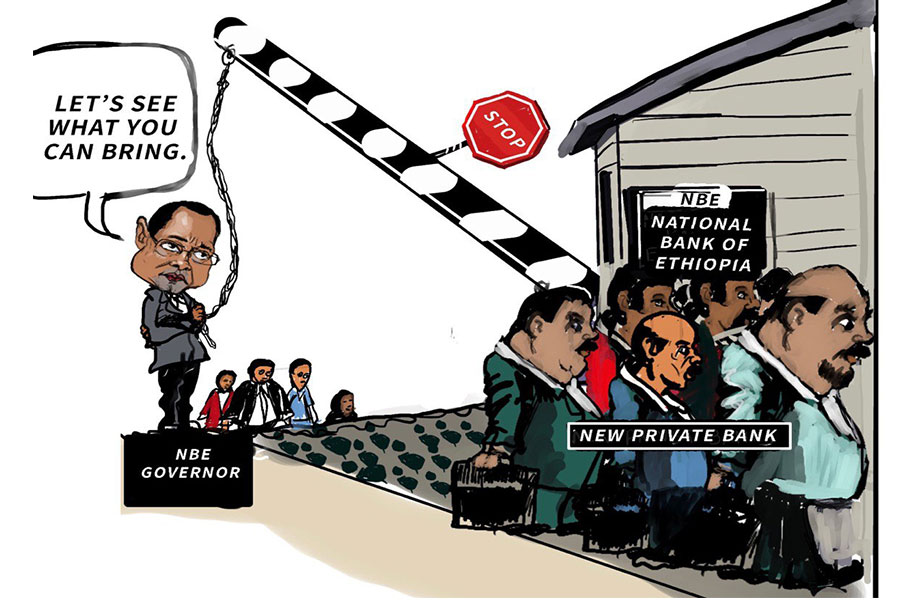

Eyob Tekalegn (PhD) had been in the Governor's chair for only weeks when, on Septembe...