Sunday with Eden | Jul 27,2019

Jul 3 , 2021

By Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn

The new proclamation on Federal Advocacy Service has introduced many changes, but the recognition of law firms is arguably the most significant. It hints at a revolution in thinking, where recognising a legal profession as a business is no longer considered to defile its sanctity, writes Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn (yehuala5779@gmail.com), adjunct lecturer at Addis Abeba University and an associate at MTA.

Advocacy as a profession has a long history in Ethiopia. The first advocates were priests. Parties to a dispute were represented by churchmen known for their rhetorical abilities after studying the Old Testament and Fetha Negast (Law of the Kings) in spiritual schools. These men were known for carrying their chairs from one place to another and practice advocating on behalf of another party after they acquainted themselves with the skill of rhetoric and oratorical ability. By that time, these people were not required to hold a license.

For the first time under the Ethiopian legal system in 1936, the right of the disputant parties to be represented by lawyers was specified. There was also a requirement for the advocate to know the law. This was further cemented by a legal notice in 1952 that indicated that advocates should hold a license. Applicants were required to have all the necessary skills and knowledge to enable them to practice the law properly.

In all these legislations, the term “advocate” was not used but rather “practice.” The latter was defined as follows: practice means, by way of a profession as a legal advisor, to conduct or plead an action, cause, suit or similar legal process before a court or before an official of a court, on behalf of another person, to write or prepare for another any act or document in a legal matter of any kind or to give legal advice.

The legal profession began to make a drastic turnaround in the 1960s for three reasons: the introduction of four substantive laws and two procedural laws, the appearance of seasoned and experienced lawyers, and foreign judges' appearance on different benches. In the late 1960s, practitioners started to form a de facto law firm based on the principle of partnership. Even some practitioners blatantly called their law offices law firms despite the fact that the authorities rejected them.

In the Imperial ear, there were de facto law firms such as Scot & Scot Law Office, run by American Lawyers that also co-opted the services of the famous lawyer Assefa Dula; Vosikis Law Office, which was run by an Italian lawyer; Hamawi Law Office run by a Lebanese lawyer; and Teferi & Bekele Law offices run by two Ethiopian foreign-trained lawyers. Tamiru Wendemagegnhu, who served as vice president of the Federal Supreme Court, has written about these practices.

However, this impressive progress was overshadowed by adopting the socialist ideology during the Dergue era that was against private ownership of property. This, in turn, led to the expropriation of foreigners’ properties and expulsion of foreigners, including foreign lawyers from the country by labelling them as “imperialist.” Moreover, as the economic situation of the country deteriorated, the legal profession was affected similarly.

After the downfall of the Dergue regime and the adoption of a more liberal form of government and liberalised economy, in 1990, an attempt was made by the prominent lawyer in the country, Abebe Worke & Associates Law Counseling Plc, to form a law firm. However, it was barred before engaging in the legal practice after the then Department of Lawyers’ Affairs brought a charge against four of the members by alleging that they had advertised for establishing a business firm.

The main argument of the Department was that the legal profession is not termed as trade within the Commercial Code. Moreover, the law firm announced its establishment on Addis Lisan, an Amharic publication, which is contrary to the legal profession and the rules of ethics governing the legal profession, according to the Department. This signalled the regime subsequent to the Dergue was not in favour of law firms.

Things changed shortly after the administration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s (PhD) bid to further open up the economy. As part of this process, the government desired to revise the existing legal profession, which was archaic for the modern world. The new proclamation on Federal Advocacy Service Licensing and Administration introduced many changes, but the recognition of law firms is arguably the most significant.

Law firms are associations of legal professionals organised to earn while rendering comprehensive and efficient legal service. They comprise partners, associates, paralegals, and other supporting staff. Through their joint and concerted efforts, they can render efficient and effective services to their clients. Moreover, professionals in law firms have different areas of specialisation. Compared to private law offices, they are well-equipped in materials and have facilities like libraries, documentation rooms, guest reception, and other facilities that are important in effectively disposing of their tasks and objectives.

Unlike private law offices, the death of a partner in a law firm will not be a cause for dissolution and disruption of the client-attorney relationship. Moreover, because of the rise of large corporate entities, both domestic and foreign, it is imperative to introduce law firms to meet the needs of business clients for legal services of unprecedented volume and complexity.

The changes made in the proclamation, more than anything else, also hint at a revolution in thinking. For the better part of legal history in Ethiopia, recognising the legal profession as a business was considered to defile its sanctity.

Under the amendments that have been made, a law firm will have a limited liability partnership (LLP) type of legal personality. Unlike the traditional concept of partnership in the Commercial Code, where there is an unlimited personal liability of its partners, in the case of LLP, the liability of the partners is limited to their financial interest in the partnership. However, the remaining features of partnership – fiduciary obligation between partners and the partnership and the right to co-manage the partnership – apply to the LLP.

Upon registration of partnership with the Office of the Federal Attorney-General, the partnership will have its legal personality distinct from that of the partners. This, in turn, implies that the partnership will have the capacity to have its name, sue or get sued, own and administer property and enter into various contracts.

The new proclamation takes things a step further in permitting the participation of foreign law firms. As a rule of thumb, one has to have a license to provide advocacy services in Ethiopia, which in turn requires the applicant to be of Ethiopian nationality or be a non-national with Ethiopian origins. Despite this cardinal principle, the proclamation recognises the participation of foreign law firms and advocates if the case has to do with the licensing country and if they work in collaboration with Ethiopian law firms or domestic license holders.

The proclamation also allows the operation of law firms in collaboration with a foreign one. It is possible to form law firms in Ethiopia with two or more advocates. It can also be done in partnership with foreign license holders or foreign firms, although the equity ownership of the foreign firm should not be greater than a quarter of the capital.

However, the new proclamation failed to open up law firms for the participation of non-lawyers. It appears to continue the monopoly of law practice by traditional professionals. As things stand now, law firms cannot be established in collaboration with non-lawyers even with limited equity participation of the non-lawyers in the firm.

This will give a chance for outside investment in law firms to provide, among other things, capital for expansion, investment in technology, new associates training and financing for contingency fee cases.

PUBLISHED ON

Jul 03,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1105]

Sunday with Eden | Jul 27,2019

Fortune News | Jun 24,2023

Advertorials | Jun 05,2023

Viewpoints | Feb 23,2019

Radar | Oct 27,2024

Commentaries | Jun 18,2022

Editorial | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | Jul 13,2020

Exclusive Interviews | Jun 01,2024

Photo Gallery | 156898 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 147190 Views | Apr 26,2019

Photo Gallery | 135755 Views | Oct 06,2021

My Opinion | 135287 Views | Aug 14,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Sep 13 , 2025

At its launch in Nairobi two years ago, the Africa Climate Summit was billed as the f...

Sep 6 , 2025

The dawn of a new year is more than a simple turning of the calendar. It is a moment...

Aug 30 , 2025

For Germans, Otto von Bismarck is first remembered as the architect of a unified nati...

Aug 23 , 2025

Banks have a new obsession. After decades chasing deposits and, more recently, digita...

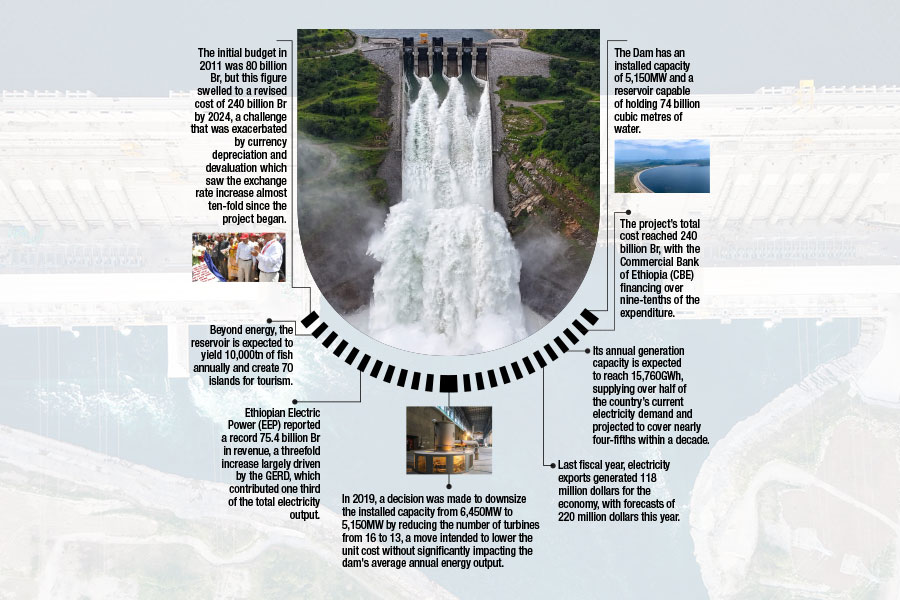

Sep 15 , 2025 . By AMANUEL BEKELE

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa's largest hydroelectric power proj...

Sep 13 , 2025

The initial budget in 2011 was 80 billion Br, but this figure swelled to a revised cost of 240 billion Br by 2024, a challenge that was exac...

Banks are facing growing pressure to make sustainability central to their operations as regulators and in...

Sep 15 , 2025 . By YITBAREK GETACHEW

The Addis Abeba City Cabinet has enacted a landmark reform to its long-contentious setback regulations, a...