My first encounter with GebreKristos Desta’s work was through his poem Yemejemeriaw Ken (The First Day). The verse brief and direct, rapidly escalates toward the climax of the story. In fewer than half a dozen stanzas, he captures the meeting of a man and a woman. Dining and enjoying glasses of what I presume to be wine, their subtle cues, flirtatious glances and playful touches culminate with them in each other’s arms.

It was amazing how, with so few words, he painted such vivid and powerful imagery. At the poem’s end was a name unfamiliar to me: GebreKristos Desta. What surprised me even more was discovering it had been authored decades earlier. I marveled at his bold, Bohemian style in an era when conservative culture and strict artistic norms dominated.

During my youth in the late 90s, encountering his works was rare. His poetry held an almost mythical allure, enchanting and illusive, a poem on a newspaper here, a radio rendition there. With no published work, it felt like chasing shadows.

That changed when I found his anthology, Menged Situgn Sefi (Give Me a Leeway), published by Addis Ababa University’s Institute of Ethiopian Studies with support from the German government. Despite the strict copyright provisions in the book, a soft copy circulates online. This raises doubts about whether the enforcement of intellectual property rights is taken seriously, especially since the proceeds were pledged to philanthropic causes.

One evening, I chanced upon my old friend Maheder Gebremedhin at our favourite hangout, La Pâtisserie Café. Over coffee, he mentioned an upcoming event at the GebreKristos Desta Center, an annual celebration and intellectual exchange honouring the poet and painter. Maheder has a knack for prodigious undertakings in fine arts and academia. It was not the first time he had tipped me off; he previously invited me to the inaugural screening of Urban Genesis, a documentary about the ambitious BuraNest project, a model sustainable town crafted by renowned Ethiopian and Swiss architects, including Professor Fasil Ghiorgis and Dr. Zegeye Cherinet.

The atmosphere at the Center was as lively. Fans, art lovers, and GebreKristos’ contemporaries filled the space. Even virtual speakers from the University of Oklahoma, where Gebre spent his final years, joined the event. Associate Professor Bekele Mekonnen, a contemporary visual artist, poet, educator and director of the Institute, served as the master of ceremonies.

He wonderfully reflected on Gebre’s life and legacy, inviting speakers who had been at the poet’s deathbed to share their memories. Unpublished letters offered novel insights into the enigmatic figure who captivated art lovers. Passionate recitations delivered by Bekele himself, famed artist Girum Zenebe, and Gebre’s two sons moved the audience. Bekele also kindly invited audience members to recite Gebre’s poems or share reflections. He reminded us that the day belonged not only to academics and art aficionados but to anyone touched by Gebre’s work.

GebreKristos’ poetry revolves around a profound love for his homeland, from which he was exiled for much of his adult life. In a radio interview, Professor Fikre Tolosa recounted GebreKristos’ final days in Lawton, Oklahoma. In a sorrowful depiction of events Fikre laments 70s Oklahoma was no place to be for a soul so deeply rooted in Ethiopia. The weather was as unforgiving as the town’s mood in the immediate aftermath of the civil rights era with Oklahoma a flashpoint. The state’s history of dislocated Indigenous Americans and a Southern slave state was no less depressing for a free and poetic soul.

In his famous poem Hagere (My Country), GebreKristos fondly describes Ethiopia’s moderate climate saying the cold is never too cold, the heat never too hot. His poetry longs for all the simple, familiar rhythms of home. From the dining culture to the bustling city streets to mundane objects like dust and taxis, his verses capture the essence of a land he yearned to return to, even in death, a fate more sacred and fulfilling than any.

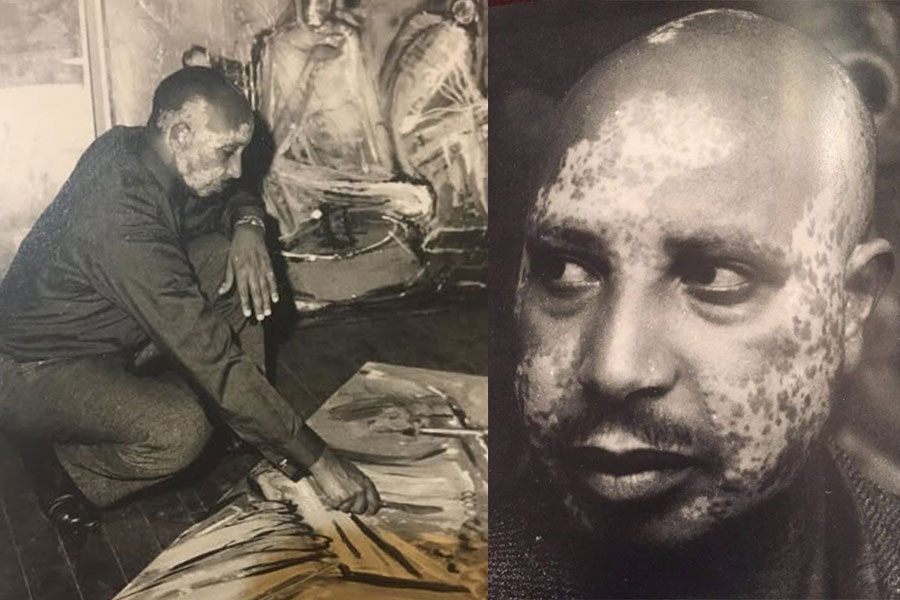

Born in Harar and raised by a single father who was a clergyman and traditional schoolteacher, GebreKristos grew up in a pious home immersed in religious and literary traditions. He excelled in Amharic and Ge’ez poetry before attending the prestigious General Wingate School in Addis Ababa. Later, he studied at the Die Schule für Bildende Kunst und Gestaltung in Cologne, Germany, where he adopted abstract expressionism. This modern style clashed with the prevailing Ethiopian and classical European artistic traditions, earning him the scorn of established Ethiopian painters. Ironically, he was equally skilled in both Ethiopian and classic styles.

As a pioneer of the Fine Arts School at Addis Ababa University, GebreKristos influenced a generation of artists, including the trailblazing Desta Hagos. Though Emperor Haile Selassie reportedly said his work made no sense to him, the monarch shrewdly recognized its significance for modern Ethiopia and became a patron.

Today, the GebreKristos Desta Center holds an invaluable collection of his paintings, with additional works scattered across private collections and institutions like the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia. The Center plays a major role in sustaining his legacy and inspiring generations. Dedicated staff like Alemtsehay Ketema, a seasoned and well-informed curator, well versed with facts about Gebre and his work also deserve praise. However, much of the credit for preserving his legacy goes to the late Andreas Eshete, former president of Addis Ababa University, who masterminded the establishment of the Center and the repatriation of Gebre’s artworks during his tenure.

The event honouring Gebre also included a contemporary art exhibition featuring emerging talents. Given that it was on March 08, International Women’s Day, two young female artists appropriately stood out: Fetlework Tadesse and Teimar Tegene. I enjoyed Fetlework’s bold, colourful pieces dominated by female characters, using gestures and body language to convey complex emotions. Her magnum opus is aptly titled “Missing Me”. It was a mesmerizing exploration of identity. At its centre was a life-sized self-portrait, fig leaf in hand, a provocative nod to the biblical Eve. Surrounding it were ethereal figures representing alternate versions of herself: an angelic being, a meditative Buddha, and a mermaid-like form suspended in water.

Teimar’s monochromatic works were no less captivating. Her intriguingly grotesque and seemingly haphazard lines and curves reveal a contrast of beautiful and serene human faces shyly peeking and teasing the viewer to appreciate their features. These emerging artists embody the spirit of GebreKristos’ innovation and carry his torch forward.

As the event drew to a close, attendees gathered for a group photo in the beautiful afternoon twilight. We all gathered on the stairway of the centre that bore the name of the legendary artist, writer and educator. Behind us stood GebreKristos’ masterpiece Golgota, which was Aramaic for Calvary. The painting, heavy with themes of exile, suffering, sacrifice, and redemption, reflects his life and all that he stood for. Just as Christ’s crucifixion fulfilled a divine mission, Golgota captures GebreKristos’ essence, his devotion to art, country, and freedom. For those who say, “what is in a name”, GebreKristos’ life and work stand as living proof to the contrary: he was, in every sense, Christ’s servant.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...