Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) appeared before Parliament last week to deliver a narrative filled with abundant optimism, stressing impressive economic growth over the past eight months. Yet, beneath the surface of these numbers lay severe financial strain, widespread deprivation, and unabated conflicts that threaten the country’s stability and welfare.

The Prime Minister opened his address by presenting encouraging revenue figures, announcing that the government had collected 580 billion Br during the reported period. However, optimism quickly gave way to reality, as he acknowledged that the government’s spending had overshadowed these gains.

“Our expenses burdened our revenues,” Abiy bluntly admitted, pointing to a range of subsidies and expenditures that have weighed heavily on the federal budget.

Fertiliser subsidies alone reached 84 billion Br; fuel subsidies amounted to 72 billion Br; social safety nets demanded 22 billion Br; and, pharmaceuticals and edible oil consumed another 350 million Br. The Prime Minister argued that these extensive subsidies were necessary but costly, contributing to the challenges of managing public finances. The economy struggles particularly due to its low tax-to-GDP ratio, which remains under seven percent, roughly half that of neighbouring Kenya’s 16pc.

“It’s one of the lowest,” he conceded. “We’re still struggling to make it grow.”

Experts estimate that if his administration had to determine whether to collect taxes matching Kenya’s ratio, the federal government would have raised no less than 2.78 trillion Br.

One major issue complicating fiscal balance is fuel subsidies. At 101 Br a litre, they have nearly doubled from last year’s figures. A full phase-out is scheduled in the next year, sparking fears among many consumers that this swift removal will exacerbate living costs and adversely affect vulnerable populations.

Economist Arega Shumete (PhD) remains concerned over the government’s subsidy strategies, noting misallocation that often benefits urban dwellers disproportionately, particularly those in Addis Abeba, instead of supporting broader rural populations.

“The government’s expenditure is confused,” said Arega.

This confusion extends beyond subsidies to critical sectors like education and health. Parliamentarians have voiced alarm over substantial budget cuts in recent years. The education budget plummeted from 123 billion Br to 55.8 billion Br in the current fiscal year, a 55pc reduction. Health sector funding shrank from 51 billion Br to 22.6 billion Br during the same period, another 56pc decrease.

“It’s unstrategic,” Arega told Fortune, warning of potential long-term risks to human capital and social stability.

Despite these troubling reductions, Prime Minister Abiy’s Administration has pushed forward with salary increases for members of the public service, particularly targeting those in lower-income brackets. Those earning around 1,100 Br monthly have received the largest raises, with adjustments ranging from 332.7pc down to just five percent for higher earners making approximately 20,468 Br monthly.

The wage adjustment, however, adds a considerable 91.4 billion Br to the public expenditure, financed partially through a recently secured half-billion-dollar loan from the World Bank, part of a broader 1.5 billion dollar International Development Association (IDA) package.

Approved by Parliament less than two months ago, the Finance Minister, Ahmed Shide stated that the loan would support social safety nets for vulnerable households, including the civil service. Yet, even this wage hike has struggled to address everyday realities many civil servants face.

Tigist Adane, a 42-year-old primary school teacher, embodies the struggle that millions face. Earning 9,000 Br gross monthly salary, she finds basic necessities increasingly unaffordable. Prices for staple items like teff, now at 15,000 Br a quintal, cooking oil at 1,600 Br for a five-litre container, and onions at 110 Br a kilogram have forced her to cut back drastically.

“My life has been worsening,” Tigist told Fortune.

Forced to relocate after her home was demolished for a city corridor project, she now contends with rising transportation costs, school fees, and housing expenses.

The gap between official optimism and citizens’ lived experiences is apparent. Despite the Prime Minister touting improved economic indicators, praising an 8.4pc projected GDP growth primarily driven by agriculture, industry, and service sectors, the bleak realities persist. Once celebrated for double-digit economic expansion, Ethiopia now faces undeniable evidence of deteriorating social conditions, echoed Desalegn Chane (PhD), an MP representing the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA).

Desalegn flagged before a quietly listening parliamentary floor data from the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index, which puts Ethiopia as home to 86 million multidimensionally poor people, roughly 7.8pc of the global total.

“People’s lives are worsening,” Desalegn lamented, directly challenging the Prime Minister’s optimistic narrative.

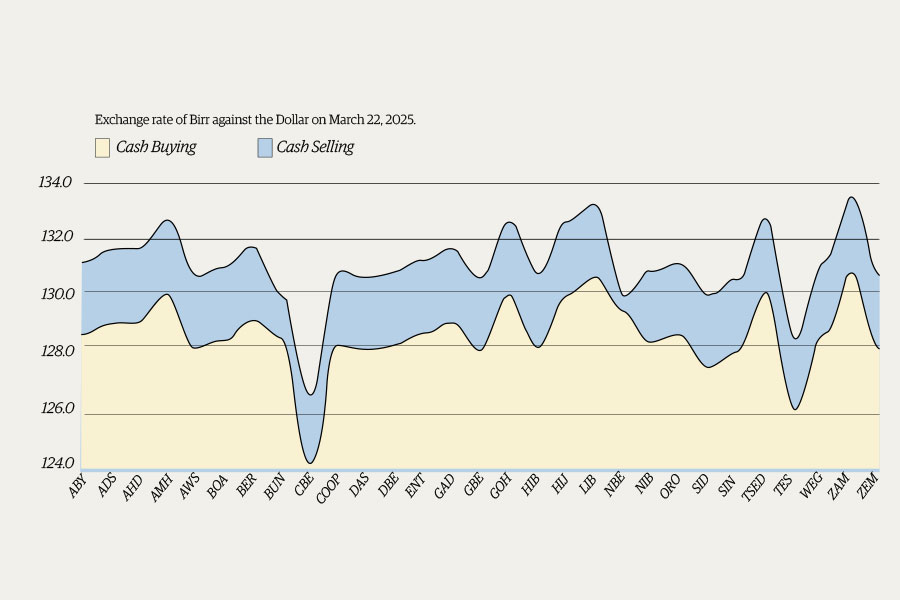

Abiy defended his Administration’s performance, stating foreign exchange revenues yielded over 14.9 billion dollars over the past eight months. Commodities exports accounted for 4.5 billion dollars, service reached 4.7 billion dollars, remittances brought in 3.7 billion dollars, and foreign direct investments totalled around two billion dollars. Imports, however, were substantial at 10.5 billion dollars, primarily driven by capital goods.

While such statistics might suggest economic vitality, scepticism lingers.

Arega, the economist, warned against accepting official data uncritically, recalling previous discrepancies in poverty assessments by the World Bank and the Ethiopian Statistical Service (ESS), which underestimated the country’s poverty rate.

“They held off the data to save face,” Arega said. “There is always the urge to make one look good by stating increasing economic growth despite realities proving otherwise.”

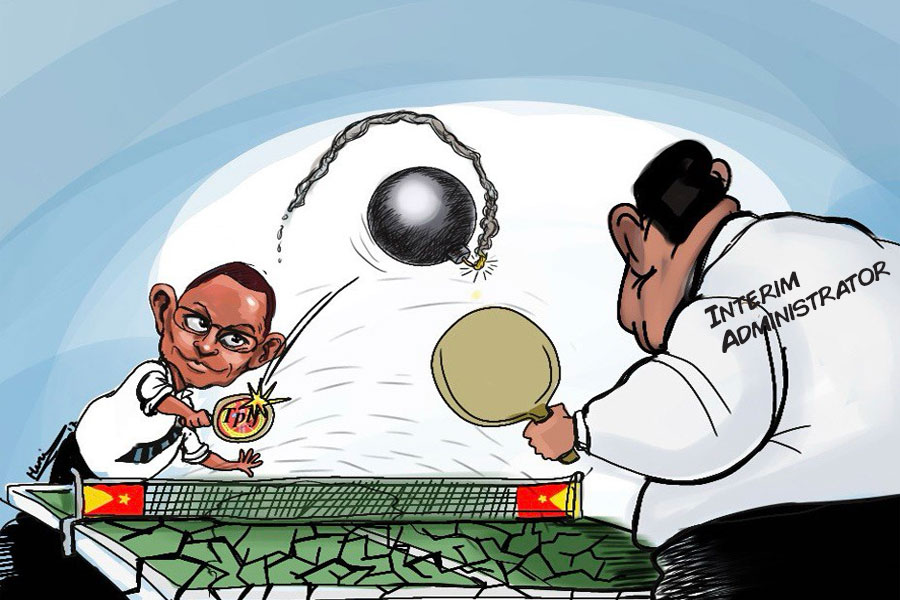

These economic contradictions are further compounded by deteriorating security and rising food insecurity. Ethiopia now ranks fourth globally in acute hunger, trailing Nigeria, Sudan, and Yemen. Nearly 15.8 million Ethiopians face severe food shortages, exacerbated by a devastating three-year drought, subsequent flooding, macroeconomic instability, and reduced humanitarian aid. Infrastructure destruction from civil wars, particularly in the northern Tigray region, has worsened poverty levels, with regional states such as Oromia, Amhara, Somali, and Afar affected by ongoing conflicts. The rising cost of fertilisers, coupled with shrinking farmland due to urbanisation, threatens agricultural productivity and rural livelihoods.

This year, the federal government allocated substantial resources — 1.3 billion dollars and 156 billion Br — for fertilisers imports and subsidies, respectively. Nonetheless, soaring global prices and currency depreciation have caused costs for farmers to skyrocket. Diammonium phosphate (DAP) fertilizer now costs 7,000 Br to 8,000 Br a quintal, while urea ranges from 5,000 Br to 6,700 Br.

Last year, the federal government spent a billion dollars on fertiliser, with subsidies reaching 15 billion Br. This year, subsidies have jumped to 84 billion Br, a staggering 253pc increase.

“We’re providing the highest subsidy in our history,” Sophia Kassa(PhD), state minister for Agriculture, said in a recent media briefing.

Badiho Birmeji, a 50-year-old farmer from Meki, in the Oromia Regional State, who supports six children, farming maize and wheat on 20hct, faces a dire dilemma. Fertiliser prices doubled this year, forcing him to halve his purchases and risk lower yields.

“It’s not just about producing enough for the market,” Badiho said. “It’s also about our own survival.”

His situation is a telltale story of the precarious conditions confronting millions of farmers who, despite government subsidies, struggle under relentless price pressures and uncertain harvests.

For Abebaw Desalew(PhD), an MP-NaMA, additional alarms are emerging over the widespread shortages caused by subsidy mismanagement, including frequent fuel shortages that force vehicles to wait days for fuel access. Wage hikes intended to alleviate civil servants’ hardships have proven insufficient, where double-digit inflation and escalating rents are the norms.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...