The brewing industry faces a storm, with barley shortages leading to a substantial spike in prices, a scenario that has prompted alarm among industrial leaders.

Barley is a fundamental ingredient in beer production, and with prices soaring from 3,000 to 9,000 Br a quintal, breweries confront hefty costs and supply disruptions. The Ethiopian Beer Producing Industrial Sectoral Association has reached out to the Ministry of Industry for intervention, arguing the centrality of barley, which forms 65pc to 80pc of beer inputs, to the sector’s sustainability and productivity.

“Barley is the lung of our industry,” said Bart De Keninck, chairman of the Association and general manager of Heineken Ethiopia Plc.

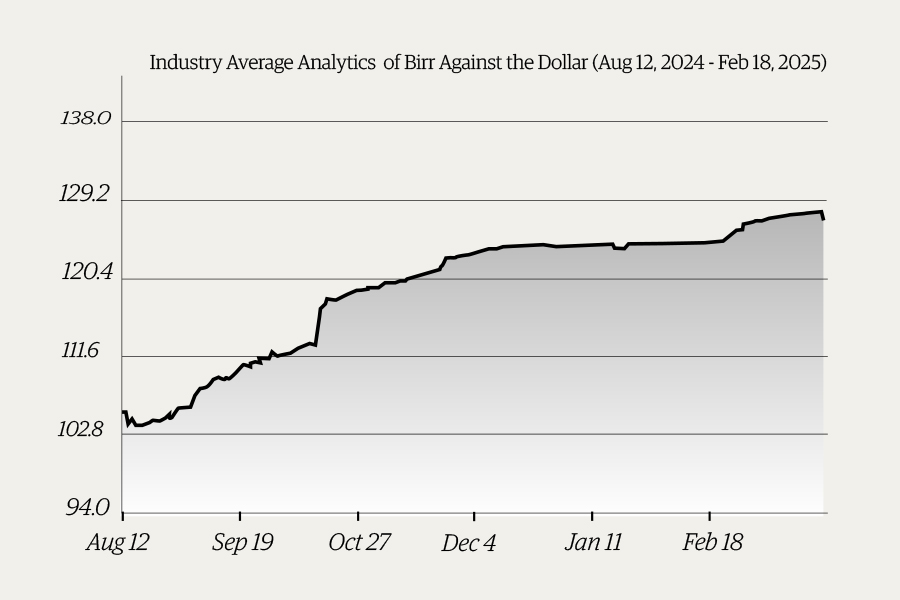

Industry leaders attributed much of the price increase and shortage to hoarding, which disrupts supply chains, slows production, and raises operational costs. As of February this year, international barley prices were 113 dollars a tonne, considerably lower than the domestic prices, making locally sourced barley among the world’s most expensive.

The beer industry’s annual barley demand is 185,000tns. Yet, by late March, malt processors had secured only 12pc of this total, although more than half of the required barley should have already been collected during the current harvesting season.

De Keninck disclosed that the Association urged the Ministry to stabilise the barley supply chain and maintain productivity. Its leaders alerted the authorities on licensed and unlicensed traders engaging in hoarding practices. They also advocate for eased import restrictions during severe shortages and closer collaboration with major barley producers and distributors.

The crisis follows recent regulatory changes that encouraged the beer industry to shift entirely to locally sourced barley by 2023. A newly introduced excise tax law imposed differentiated rates, favouring breweries using locally sourced barley. Companies using at least 75pc local barley face a 30pc tax or eight Birr a litre. Those exclusively using local barley are subjected to 35pc or nine Br. Beer producers dependent on imported barley pay the highest rate of 40pc (11 Br).

Such regulatory measures prompted major industry players, like Heineken and Malteries Soufflet, to launch extensive programs offering seeds, training, and funding to thousands of local barley farmers. These initiatives increased local barley production and improved farmers’ livelihoods. Despite these efforts, recent alleged hoarding and trading disruptions have reversed gains, forcing malt producers and breweries to reconsider importing barley again.

Unlike many countries, Ethiopia’s beer market is dominated by five companies – BGI Ethiopia (Castel Group), Heineken Ethiopia, Dashen Brewery, Habesha Breweries, and United Beverages, which together control the vast majority of beer production, with a total capacity of 21 million hectolitres. After a string of acquisitions, BGI Ethiopia operates the most breweries (six recently), and Heineken runs three plants. It has the capacity of producing 5.3million hectolitres annualy. Dashen (majority owned by UK-based Vasari) and Habesha (part-owned by Netherlands-based Bavaria-Swinkels) have also expanded capacity in recent years.

With a 40pc market share, Heineken Ethiopia has particularly felt the strain. Entering the Ethiopian market 12 years ago through acquisitions of Harar and Bedela breweries, the company gradually transitioned to local barley, increasing its sourcing from just three percent in 2013 to 100pc by 2023. In 2023 alone, Heineken Ethiopia contributed 9.7 bllion Br in taxes.

However, its executives worry that the barley shortage could undermine these gains, pushing the company and others back towards importing.

Heineken, heavily dependent on barley from West Arsi and Bale in Oromia Regional State, meets nearly half its barley needs and expects a 50pc shortfall by year-end. The remaining supply is sourced from the Sidama Regional State and Gurage Zone in the Southern Regional State.

Similarly, Habesha Brewery, established by 8,000 shareholders in 2009 and operational since 2015, also faces severe shortages. According to Surafel Bogale, Habesha’s technology manager, their midseason barley collection is 60pc below target. The price surge has also hurt them, with barley prices jumping from 55 Br a kilogram to over 100 Br in recent months. Surafel noted that imported barley costs less despite the tax advantages favouring local sourcing.

“It seems they have taken the market for granted,” Surafel told Fortune, calling for immediate action by the authorities and revisiting excise taxes.

For tax expert Biruk Nigusse, excise taxes are designed to boost revenue and discourage certain products, including alcohol. However, he called for policy intervention, such as facilitating barley imports, should shortages become evident. Biruk stressed the importance of the brewery industry, noting that brewing companies contribute around 20pc of total profit taxes, making their financial health vital to federal revenues.

Soufflet Malt Ethiopia, which started operations in 2017 with a 50 million dollar investment, now faces similar shortages. The company’s malt processing plant, capable of handling 800,000Qtls annually, secured only 25pc of its barley needs halfway through the harvest season. Its Deputy Supply Chain Director, Tesfaye Bedada, blamed hoarding and “illegal trading” for disrupting supplies. Although prioritising local sourcing, the company begins to consider imports.

At the heart of the barley shortage lies the shift by many farmers towards wheat cultivation, driven by better pricing and profitability.

According to Abdurahman Haji, head of Galema Farmers Union, representing 74,000 farmers in Oromia Regional State, last year barley sold for 2,500 Br a quintal compared to wheat at 5,000 Br, prompting nearly 30pc of his members to switch crops. The Union, which supplied over 100,000Qtls of barley two years ago, collected one-tenth of this volume this year due to lower yields and fewer farmers growing barley.

“Farmers go to where the profit is,” said Abdurahman.

Agroeconomist Marelegn Adugna (PhD) advocated boosting barley production through strict contract farming agreements, ensuring breweries provide necessary inputs to reduce farmers’ production costs. Marelegn urged breweries to raise barley purchasing prices to encourage sustained barley farming, and proposed contract prices would adjust according to market rates.

“The farmer should be prioritised,” Marelegn told Fortune.

But, farmers like Abdurahman blame contract farming initiatives as ineffective despite market volatility.

Million Beza, general manager of Highland Green Farm in Bale, confirmed that last year’s low barley prices prompted his company to gamble on barley, reaping profits as prices surged. Highland Green sold barley at 8,600 Br a quintal, a sharp increase from last year’s losses when production costs of 3,500 Br exceeded the selling price of around 3,000 Br. Million urged enhanced government support for inputs such as fertiliser and technical guidance to optimise productivity.

However, despite widespread concerns over declining production, Oromia’s State’s Agriculture Bureau officials dispute any major shortfall. Deputy General Berisso Feyesa claimed the region’s barley production slightly increased this year, reaching 15.6 million quintals from half a million hectares. Instead, Berisso attributed shortages primarily to illegal hoarding and trade, urging intensified legal actions against traders and non-compliant farmers. He confirmed yields average around 35Qtls a hectare.

The Ministry of Agriculture reported that last year’s barley harvest replaced imports valued at 283 million dollars. The Arsi Zone alone allocated 177,000hcts for barley, expecting around 6.9 million quintals, alongside 451,000hcts for wheat, projected to yield 16 million quintals.

Officials of the Ministry of Industry are investigating the causes of the alleged barley hoarding and shortages, forming a taskforce under State Minister Hassen Mohammed. Amarkegn Em’kulu, head of the Ministry’s input desk, acknowledged recent demands after a year without imports, confirming barley price increases compared to last year. The Ministry plans to table the issue before the macroeconomic committee, chaired by Girma Birru, special economic policy advisor to the Prime Minister, initiating comprehensive research on barley production capacities and market dynamics.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...