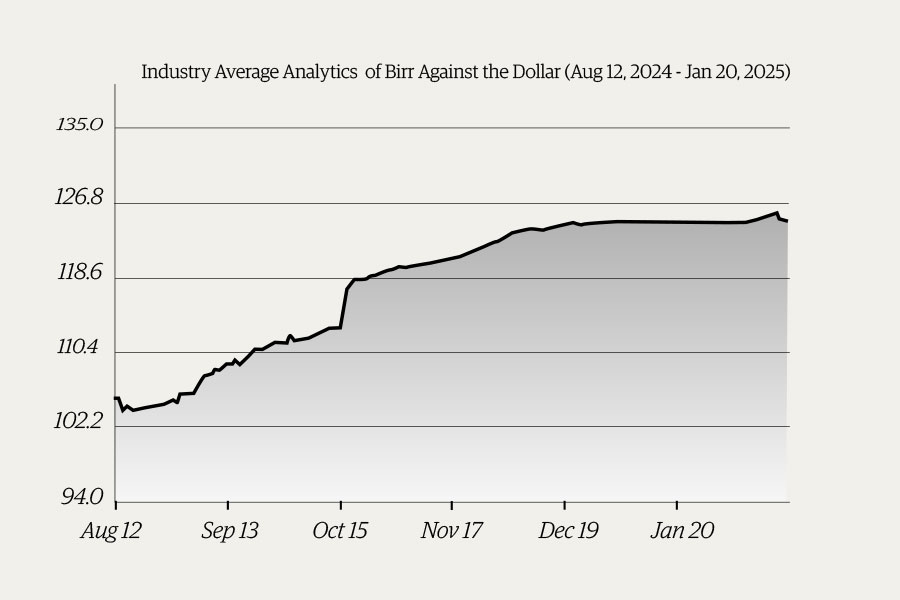

It is official. The formal forex market has the private big five banks — Awash, Abyssinia, Dashen, Wegagen, and Zemen — offering buying rates for a dollar last week that exceeded the “psychological” mark of 125 Br. The average buying rate for the Birr was 125.42 Br, while selling rates averaged 127.93 Br. A regulatory-set two percent spread is seen across most commercial banks.

However, the Birr (the Brewed Buck) reached a historic milestone when the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) posted a weighted average of 126.54 Br, an unusual move for a regulatory body perceived as a stabilising force. The Central Bank’s role during last week cannot be overstated. Setting a record-high buying rate not only surpassed all commercial offers but also signalled a possible strategy to influence the forex market’s trajectory. Market watchers believe this aggressive position may be a tactical response to persistent foreign exchange shortages, while others saw it as a deliberate effort to steer market expectations.

The forex market presented a mixed picture in the week beginning February 17, 2025. Most commercial banks maintained the typical two percent spread, but the Central Bank stood out with elevated rates coupled with an unusually narrow spread of 0.68pc. According to analysts, the reduced spread tells an interventionist policy, perhaps relieving liquidity pressures or curbing volatility.

The Birr’s depreciation reflected ongoing strains from limited hard currency availability, higher import bills, and sluggish foreign exchange inflows.

Commercial banks followed a familiar rhythm, with the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) consistently offering the lowest buying rate, at 124 Br to the dollar, consolidating its conservative position. CBE’s recorded role in stabilising the market by providing competitive rates could be targeting and attracting forex inflows. Hijira Bank (HIJ), at the other end of the spectrum, maintained the highest offers, with buying rates peaking at 126.21 Br and selling rates reaching 128.73 Br. Amhara Bank (AMH) was not far behind, posting a selling rate of 128.52 Br.

While most banks stuck to narrow rate differentials, outliers like the CBE and NBE followed divergent tactics. The CBE’s conservative strategy may reflect a bid to shore up reserves, possibly to address government priorities or guarantee critical imports. Yet, the Central Bank’s more aggressive posture has raised questions about the current monetary policy direction and the underlying pressures driving exchange rate decisions.

Over the past week, the widening gap quoted by commercial banks could amplify distortions and encourage parallel market activities, particularly among parties seeking the most advantageous deals. Although the private banks have generally maintained stable spreads, the Central Bank’s unconventional move stood out. With forex in short supply, the evolution of these rates bears watching, as any shift in policy or rate differentials could intensify uncertainty in an already tight market.

Persistent depreciation can weigh on businesses relying on raw material imports and increase the burden of external debt obligations. Market observers caution that if the Brewed Buck’s slide continues, the economic repercussions may extend beyond import prices and consumer costs. Any uptick in parallel trading could erode the effectiveness of official channels, challenging the authorities’ ability to manage liquidity and curb inflation.

Most market watchers agree that the coming weeks will be crucial for gauging the strength of the Central Bank’s current position to restore equilibrium.

Loading your updates...

Loading your updates...