Fortune News | Dec 19,2021

Mar 13 , 2021

By Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn

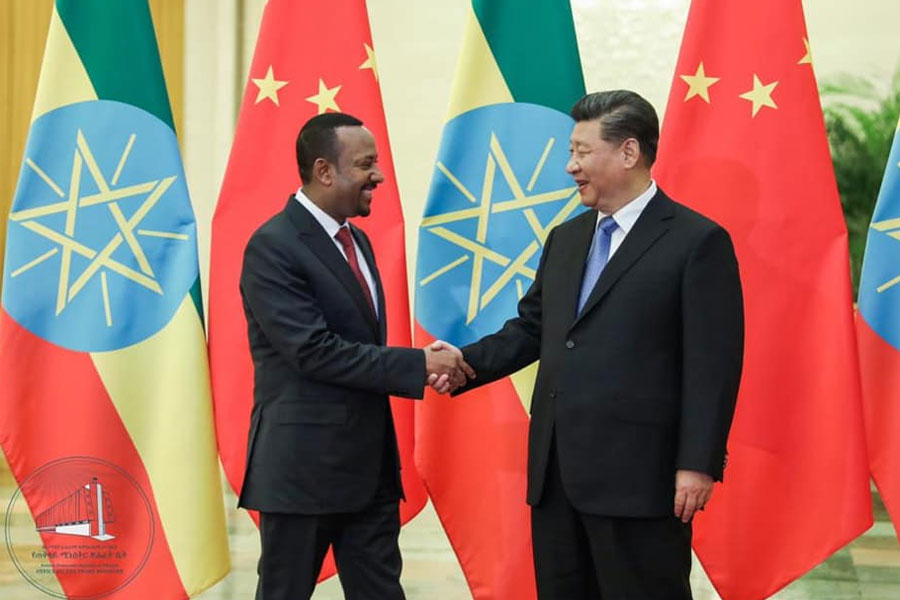

Considering Ethiopia's path to development and national interest, it should look further east, to China, as a model as it develops a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) more conducive to its circumstances, writes Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn (yehuala5779@gmail.com), adjunct lecturer at Addis Abeba University and an associate at MTA.

Since 2018, the government has been revising Ethiopia’s bilateral investment treaties (BITs), an agreement between two countries for reciprocal encouragement, promotion and protection of investments in each other’s territory by companies based in either country. It is a clear position that none will be ratified nor extended until a model is developed. However, among the most influential BITs, which one Ethiopia should adopt is hard to answer.

The policy justification for BITs is different among countries. Developing or capital importing countries and developed or capital-exporting countries have diverging aims. For developing countries such as Ethiopia, the main rationale is to secure foreign direct investment (FDI). Developed ones eye BITs that offer the best arrangement for protecting their investments and investors from political risk.

Classified as a least developed country, Ethiopia should offer the most favourable terms without conceding to attract scarce resources, money, that non-national investors have and are willing to invest. With this in mind, the examination of model BITs should lead us to assume that China’s model BIT best meets the circumstances of Ethiopia as opposed to countries such as the United States and India.

One of the most significant portions deals with the treatment of foreign investors. China’s model provides for a most-favoured nation treatment (MFN) when it says non-national investors’ activities shall not be treated in less favoured terms to that of its own investors. It also states that if any treaty covers a free trade agreement, customs union, economic union, or any international treaty related to taxation and any arrangement for facilitating small frontier trade in the border areas, it will not be covered under the MFN principle. This means any benefits extended to third parties emanating from those arrangements will not be extended to other investors.

It is quite pragmatic for Ethiopia to have such a clause in her BITs. More importantly, this model also provides a caveat even by way of a clawback clause. This means the government will have the policy space to enact any laws.

The Indian and USA model also provides that investors shall not be accorded less favourable treatment than is given to domestic investors. Nonetheless, especially concerning India, the provisions are too subjective and technical, which narrow down the fair playground for foreign investors. On top of this, the government's financial assistance to domestic investors is not considered tantamount to violation of the treaty. For Ethiopia, such a clause will have a counterproductive effect on FDI, not to mention will fail to embody the MFN standard.

When it comes to dispossession, all three models envision the possibility of expropriation or nationalisation. In China’s case, expropriation is prohibited unless the presence of public interest, in compliance with domestic procedure, is demonstrated. The close reading of this model BIT reveals that it envisages only direct expropriation. This is fitting for Ethiopia since indirect expropriation is very elusive and usually manipulated by investors. Moreover, indirect expropriation minimises policy space for the host country.

Likewise, in principle, the US and Indian models prohibit expropriation unless there is an existence of public purpose, non-discrimination and compensation. The type of expropriation envisaged is also both direct and indirect expropriation. Moreover, the standard of compensation of India’s opts for “adequate compensation” that reflects fair market value. The United States opts for “fair market value” with adequate, effective and prompt compensation.

Clearly, China’s model advocates for lower than market rate compensation, which is most appropriate to Ethiopia’s capacity.

Any BIT worth its name will also need to consider provisions concerning dispute settlement mechanisms both for state-to-state and state-to-investor disputes. In all three models, it is clearly stated that disputes between states should be solved amicably through consultation, while arbitration is considered as the last option.

Concerning state-to-investor disputes, China’s model provides for an escalation clause in which the diplomatic option comes first, followed by arbitration as a last resort. Whereas, in India and the United States, there are quite significant procedural and substantive barriers put in place. For instance, before submitting concern for arbitration, investors are expected to provide notice and exhaust local remedies.

On substantive barriers, there is an ouster clause that precludes the arbitral tribunal to examine matters linked to public interest, review of the decision of the local authority and taxation. Furthermore, there is a denial clause that enables a state to refuse to comply with the arbitration award to make things worse. As per these models, the arbitration tribunal is expected to conduct a public hearing. This might lead to the exposure of some commercially sensitive information. On top of this, the burden of proof is imposed on investors.

Last but not least, in developing a model BIT, it is important to consider how termination clauses work. International treaties are based on the free and full consent of the contracting parties. Thus, any party may withdraw from the treaty as long as it complies with the procedure set forth.

All three models embody provisions regarding the termination of a BIT. China’s BIT includes a presumption of continuity unless the other party provided a notice to terminate their relationship. This clearly shows foreign investors to what extent the country is making a serious commitment. This, in turn, creates predictability and stability. A sunset period of a decade is also provided, which is relatively long for foreign investors to mull their choices.

India uses the presumption of termination unless the other state party provides a notice to continue and renew their relationship. Moreover, the country’s model provides for a much lower sunset period, creating uncertainty for foreign investors.

These are not the only flaws to models resembling those of the US and India. The latter, for instance, has various exceptions that are too general and subjective, which leaves substantial discretionary power for local authorities on issues like domestic social issues. In the US, the country may deny any benefit if the other contracting state does not maintain diplomatic relations. This requirement makes investors’ rights contingent upon good diplomatic relations.

Considering the path to development and national interest should dictate that Ethiopia look further east, to China, as a model as it develops a BIT more conducive to its circumstances.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 13,2021 [ VOL

21 , NO

1089]

Fortune News | Dec 19,2021

Fortune News | Jan 26,2019

Fortune News | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | Jul 10,2021

Viewpoints | Nov 23,2019

Fortune News | Dec 27,2018

Fortune News | Jun 29,2019

Fortune News | Jul 18,2020

Editorial | Jun 17,2020

Radar | May 20,2023

Photo Gallery | 96133 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 88395 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 66994 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65716 Views | Oct 02,2021

My Opinion | Apr 13,2024

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 13 , 2024

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te'azaz Road (Arat Kilo)...

Apr 6 , 2024

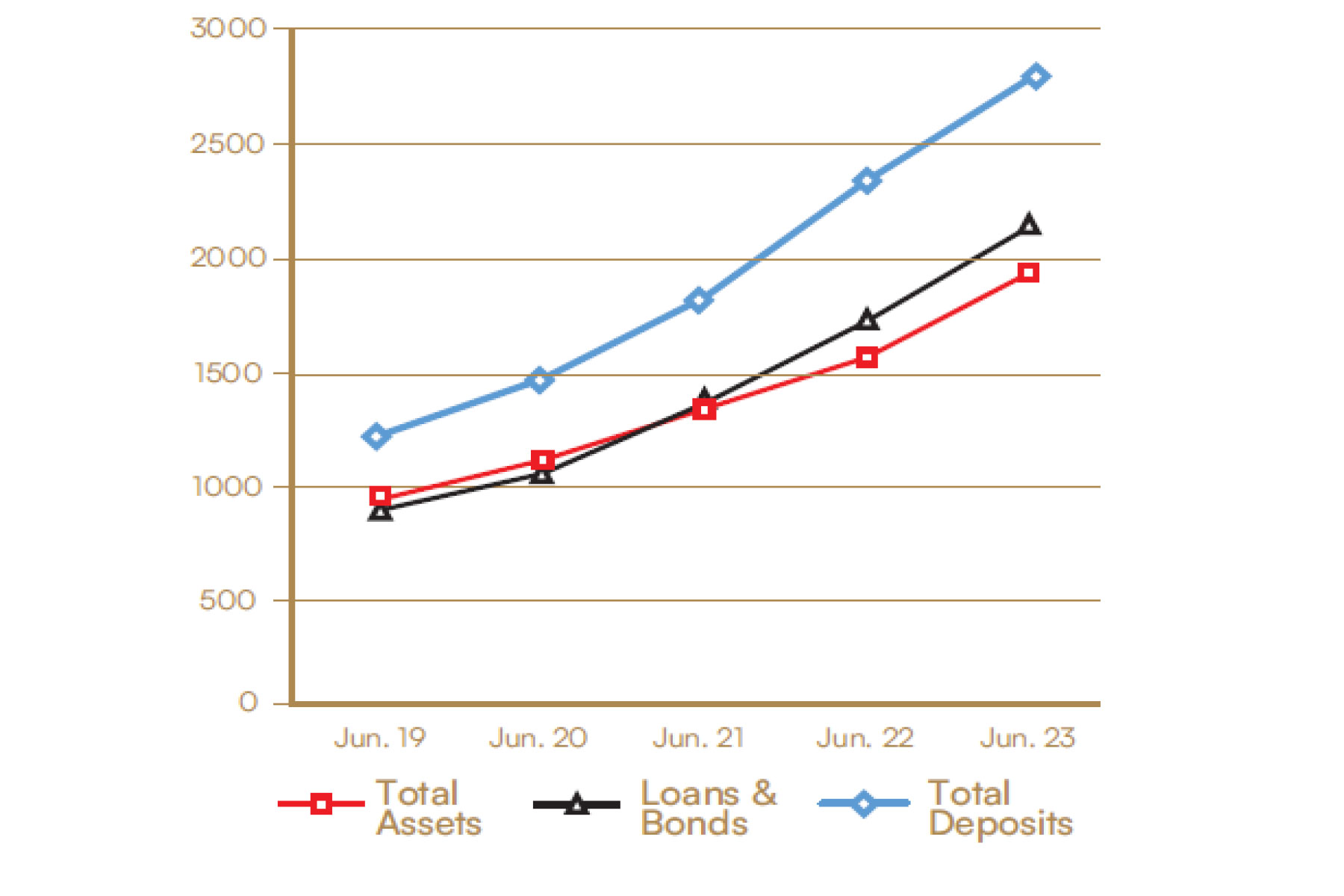

In a rather unsettling turn of events, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (C...

Mar 30 , 2024

Ethiopian authorities find themselves at a crossroads in the shadow of a global econo...

Mar 23 , 2024

Addis Abeba has been experiencing rapid expansion over the past two decades. While se...

Apr 13 , 2024

A severe financial stranglehold has been imposed on the banking industry, underminin...

Apr 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In an unprecedented move, the central bank has published its inaugural stress test report, uncovering potential fault lines within the finan...

Apr 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In a bold departure from its historical position on foreign investment, the federal government has opened...

Apr 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

A proposed excise tax stamp system draws controversy amongst industry leaders in the alcohol, tobacco, be...