Radar | Dec 25,2018

Apr 30 , 2021

By Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn

The amendment made to the Commercial Code has significantly changed the bankruptcy regime. It is no longer punitive but a means of rehabilitating businesses in trouble, writes Yehualashet Tamiru Tegegn (yehuala5779@gmail.com), adjunct lecturer at Addis Abeba University and an associate at MTA.

The intention of any business is to make a profit. But loss and failure may happen in the course of doing business and hence, there is always a possibility of bankruptcy. The fundamental issue in bankruptcy is that there is insufficiency of assets whereas many creditors claim payment.

“Not only is there no free lunch, there is not enough lunch to feed everybody, in most cases, there is no lunch at all,” as J. Herbert, one of the leading bankruptcy scholars of his generation, once said.

The main goal and purpose of modern bankruptcy law is to provide equitable, if not equal, and expeditious distribution of the assets of the bankrupt debtor among his creditors and for his discharge from his debts.

Despite no explicit statement of a policy expression, the old bankruptcy regime in Ethiopia prefers bankruptcy proceeding over the scheme of arrangement and re-organisation. It prefers a punitive approach over rehabilitation. This can be inferred from the very organisation of the Code in which most of the provisions deal with bankruptcy proceedings rather than reorganisation and restructure. It considers business failure as blameworthy and a punishable offense rather than a simple accident of commercial life that needs correction.

The recently revised Commercial Code has made a drastic policy shift in this regard. It considers bankruptcy proceedings as a means to manage financial distress and to do the best job possible by preserving what can be saved for the benefit of the debtor, creditors, and others whose interests are impacted by the debtor’s financial circumstances. The underpinning goals and policies behind the bankruptcy regime under the revised Commercial Code are the protection of debtor and creditors' interests; collective and comparable treatment of creditors; and the preservation of estate and business. Most importantly, it aims to provide a fresh start for the debtor.

The first and foremost change within the code is discharge - the legal forgiveness of the balance of debts that are not paid in full in the bankruptcy case and in which the creditors would be barred from seeking payment. Even in the absence of consent from creditors, the debtor has the right to receive a discharge as a matter of law. This is one of the features that distinguish the revised law from bankruptcy proceedings under the previous Code. From the debtor’s perspective, discharge is the principal incentive for seeking bankruptcy relief.

However, subsequent bankruptcy filings within a brief period are likely to be more than the result of just economic misfortune. The debtor may try to abuse the system. There would need to be regulatory policing against this. Moreover, there are categories considered non-dischargeable, such as debts related to taxes and duties, those arising from the dissolution of marriage, maintenance, and criminal penalties. Ironically, the law does not make fraudulently incurred obligations non-dischargeable expenses.

The other major change is the options available for the debtor. Under the previous Code, options available for a distressed debtor were limited to liquidation and the scheme of arrangement. The revised Code, however, expands the options to include reorganisation and prevention restructuring proceedings. Unlike the liquidation option, which was the main bankruptcy proceeding under the previous law, the reorganisation option offers the debtor in possession of the business the opportunity to rehabilitate and to continue as a going concern. The debtor is entitled to apply for a reorganisation plan if he/she is either not in cessation of payments or has been in termination of payment for less than 45 days. The debtor shall present a reorganisation plan in the observation period, which is four months long. This period may be extended depending on the size, complexity, and progress of the negotiation process. The key part of reorganisation process is the tripartite classes of creditors: secured, unsecured and statutory (priority creditors) and “impairment or affected” criteria.

The reorganisation plan shall be submitted to the vote of each class of creditors. The law assumes that the reorganisation proposal is accepted if one or more creditors, which represents at least two-thirds of the claims in each class of creditors, have voted in favour of the reorganisation plan. If this is not reached, the majority of the affected or impaired class may vote in favour of the proposed plan or at least one of the classes of creditors which would not receive any payment or interest votes in favor of the proposed vote. This process is introduced based on compelled compliance of the creditors which is universally referred to as the “cramdown” method.

Yet another significant change is with regards to the automatic stay - an injunction that arises by operation of law immediately upon the commencement of the bankruptcy case. The very act of filing the bankruptcy petition is the only factor for this. The whole purpose of the stay of proceeding is to secure the equitable treatment of creditors. As a matter of rule, the stay order binds all parties, and it remains until the end of the bankruptcy proceeding. Notably, if the court dismisses the bankruptcy application, the creditors will have the right to enforce their rights individually. However, the revised Code creates a “haven spot” for the debtor by not incorporating an exclusion clause for criminal prosecution and proceeding. As it stands now, the bankrupt debtor may file bankruptcy to avoid criminal sanctions.

No less important a change is on the scope of application. Under the previous legal regime, bankruptcy was limited to traders in expressed economic activities. It excluded non-traders. Nevertheless, the revised Code expands the scope to include natural persons exercising independent professional activities and craftspersons. These are individual debtors that own a business as a sole proprietorship and incur debts in commercial activities - they now fall within the bankruptcy regime.

These changes have rehabilitated the bankruptcy regime into one that is designed to support businesses instead of punishing them. It prepares the country for the private sector pivot it is trying to make by creating a more favourable investment environment.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 30,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1096]

Radar | Dec 25,2018

Life Matters | Apr 24,2021

Viewpoints | Nov 04,2023

Fortune News | Mar 12,2020

Radar |

Photo Gallery | 95838 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 88120 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 66903 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65690 Views | Oct 02,2021

My Opinion | Apr 13,2024

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 13 , 2024

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te'azaz Road (Arat Kilo)...

Apr 6 , 2024

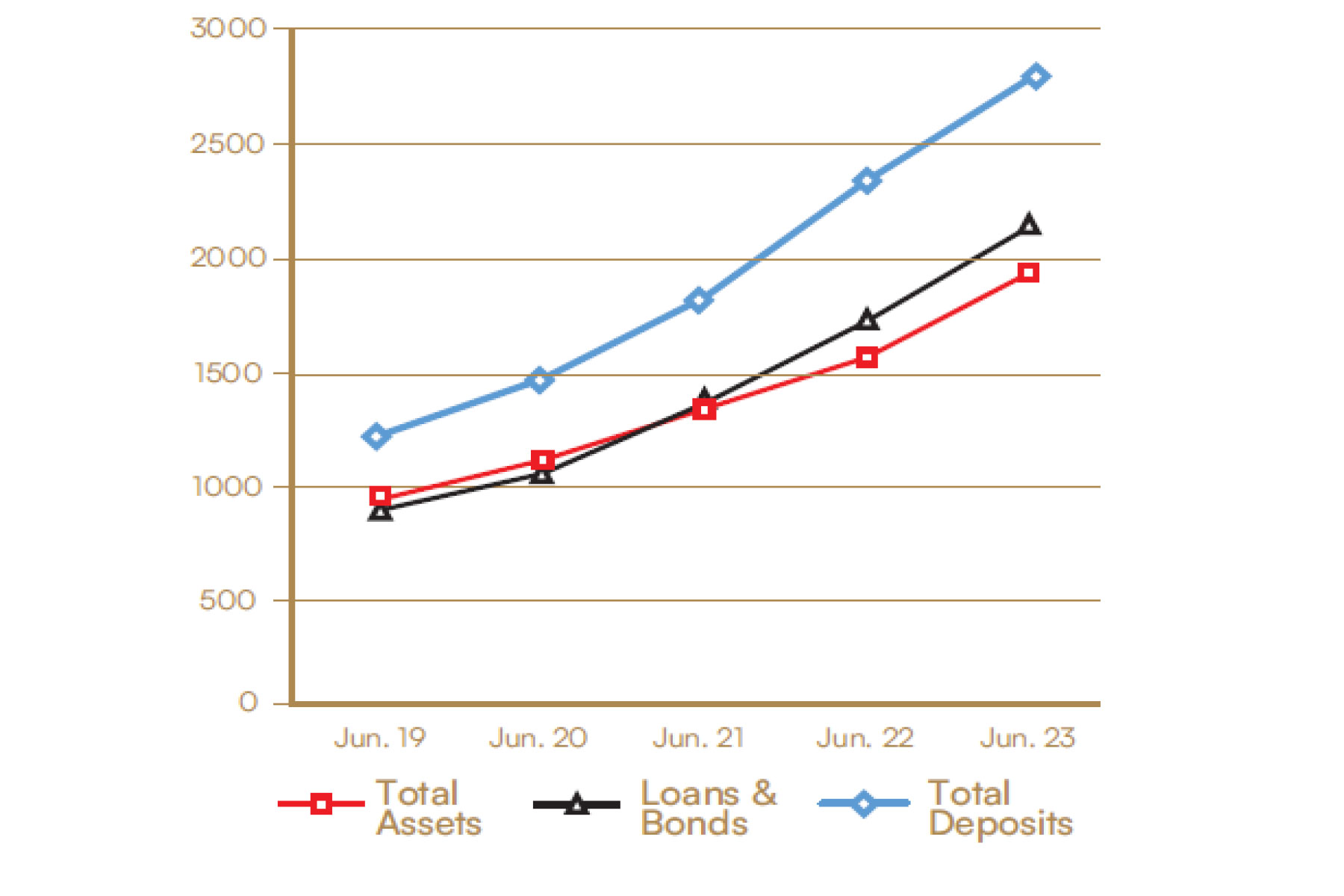

In a rather unsettling turn of events, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (C...

Mar 30 , 2024

Ethiopian authorities find themselves at a crossroads in the shadow of a global econo...

Mar 23 , 2024

Addis Abeba has been experiencing rapid expansion over the past two decades. While se...

Apr 13 , 2024

A severe financial stranglehold has been imposed on the banking industry, underminin...

Apr 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In an unprecedented move, the central bank has published its inaugural stress test report, uncovering potential fault lines within the finan...

Apr 13 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In a bold departure from its historical position on foreign investment, the federal government has opened...

Apr 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

A proposed excise tax stamp system draws controversy amongst industry leaders in the alcohol, tobacco, be...