My Opinion | May 16,2020

Mar 19 , 2022

By Christian Tesfaye

A tax that has been becoming more burdensome has been imposed on households across Ethiopia. It is eating more and more of their income. Consumption of basic goods as a percentage of income has been increasing because of this tax, leaving people with ever falling disposable incomes. The punishment is cruel and long-lasting as households are finding it hard to afford food, education and health services.

But what type of tax? When did it start being levied? Is it consumption or income tax?

It is a consumption tax. But there would typically be an exemption on basic goods such as medicine; this time around, this is not the case. Nothing is spared. Worse still, this tax was never announced, discussed between stakeholders or signed into law by parliament. It is an unofficial tax, but few call it as such. Instead, it is called inflation.

It has been a while since headline inflation peaked beyond 30pc, while food inflation sometimes cracks the 40pc ceiling. The latter one is most concerning, for obvious reasons, as well as being harder to address for households. It is perfectly possible to cut back on furniture or clothing expenses. Food is another matter. More and more people are forced to cut back on meat and dairy products, while others are forced to skip a meal or two.

There is a range of reasons why this is happening. Everybody has something to blame. Some do not make sense and are usually politically motivated, racist or xenophobic, so there is no need to waste time on them. But other factors do make sense.

The most obvious for people to see is probably the gradual lifting of subsidies, especially on fuel imports. Others, less insightful but not totally illogical, blame intermediaries that exploit temporary shortages. More perceptive persons say that it probably also has to do with global supply chain disruptions and the Russia-Ukraine crisis, which has sent commodity prices soaring. Good economists will point to the government’s expansive spending and even inflation expectation, especially by high-income households dumping their Birr for assets such as vehicles and homes (but because the construction industry has slowed down, the Addis Abeba property market is probably in a bubble).

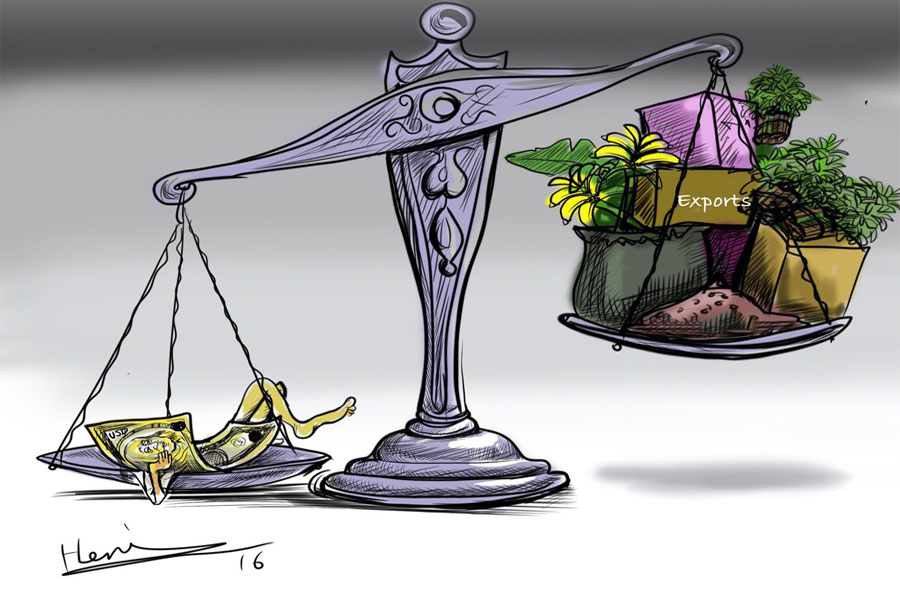

All of these are reasons for inflation to varying degrees. Historically low production capacity and expansionary fiscal and monetary policy are combining with global commodity price jumps, forming a poisonous cocktail for middle- and low-income households. On top of all of this, add the value of the Birr being devalued daily and guaranteeing that imports continue to be expensive – a suicidal policy by the central bank for the Ethiopian economy at this point.

But knowing why it is hard to address inflation in the short term will not make people less hungry or angry. The less food people have in their stomachs, the harder it is to be foresighted. They get sour and bitter. First, they will start blaming non-nationals. Look no further for proof of this than how people complain about Eritrean migrants in condominium housing every time rent goes up – a xenophobic grumble.

Then they would start to turn on one another. This has always been the script. First, there is a food emergency, then comes the resentment and the whole thing climaxes into a socio-political crisis that could end up in conflict and wars. Take the Arab Spring as an example. In the mainstream, we were told that it was the moment several countries in the Middle East and North Africa rose up incensed by the lack of democracy. There is no way of telling if indeed that was the case but this was likely the Western media projecting its norms and values on those countries.

Instead, tracing its beginnings, signs point to the rise in the cost of living. The catalyst was self-immolation by a Tunisian street vendor that could not take any more economic hardship as he struggled to feed his family. This poured fuel on feelings, perceived or otherwise, of economic inequality and injustice. The rest is history.

People are finding it hard to cope with the cost of living in Ethiopia. The government needs to act. It needs to show that it is actively looking for means to address this crisis and that it feels every bit of the burden placed on households. Time is ticking.

PUBLISHED ON

Mar 19,2022 [ VOL

22 , NO

1142]

Photo Gallery | 96491 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 88772 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 67113 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65744 Views | Oct 02,2021

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 20 , 2024

In a departure from its traditionally opaque practices, the National Bank of Ethiopia...

Apr 13 , 2024

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te'azaz Road (Arat Kilo)...

Apr 6 , 2024

In a rather unsettling turn of events, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (C...

Mar 30 , 2024

Ethiopian authorities find themselves at a crossroads in the shadow of a global econo...

Apr 20 , 2024

Ethiopia's economic reform negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are in their fourth round, taking place in Washington, D...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By BERSABEH GEBRE

An undercurrent of controversy surrounds the appointment of founding members of Amhara Bank after regulat...

An ambitious cooperative housing initiative designed to provide thousands with affordable homes is mired...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Ethiopia's juice manufacturers confront formidable economic challenges following the reclassification of...