My Opinion | Mar 06,2021

Sep 7 , 2019

By Clay Webster

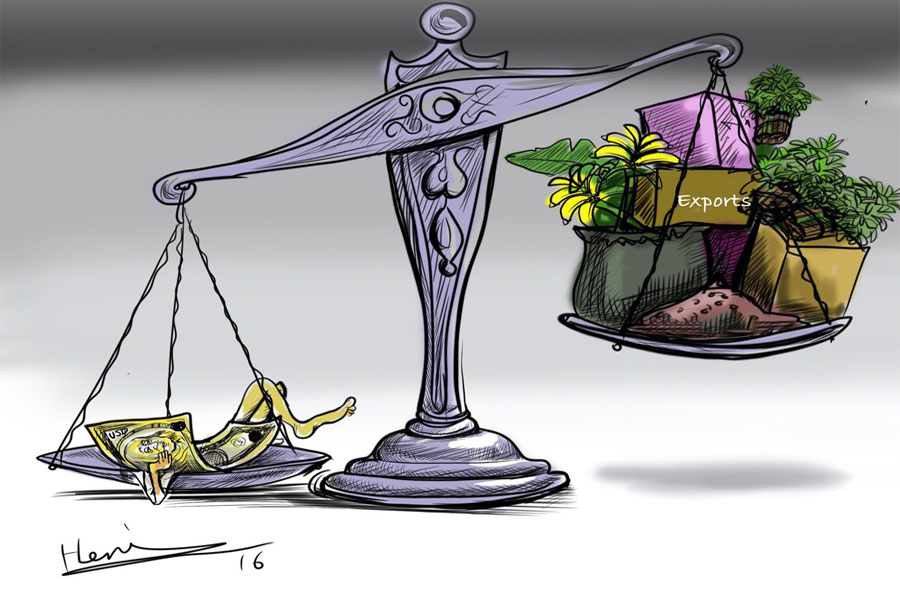

The forex crunch. At this point, it has almost become an afterthought. Not a month goes by without another news story mentioning how a lack of forex has stalled another investment project, forced a factory to run at half its capacity or idled construction workers at a building site. In many ways, it is the new normal.

And though the crunch has subsided slightly over the summer, this new normal appears here to stay. In the just ended fiscal year, Ethiopia spent 12.7 billion dollars more on imports than other nations spent on Ethiopia’s exports. With that in mind, the government has made boosting export sectors of the economy one of its top priorities with the aim of increasing the supply of forex. But on the opposite side of the equation, the government seems less imaginative in formulating policies to reduce overall demand for forex.

Earlier this year when central bank Governor Yinager Dessie (PhD) spoke to parliament, he said the government may have to direct forex only to purchases of oil and medicine. While that may become a last resort in the short run, the long run strategy would naturally be to substitute imports with locally-produced goods.

In fact, the government is already doing this with passenger vehicles. Many a car owner has felt the pain of paying import taxes in excess of 200pc on their often well-used passenger vehicle. But these high taxes have made it possible for a burgeoning domestic vehicle assembly industry to take hold.

While the nation waits for that industry to reach quality parity with the vehicle import market, both domestic and imported vehicles continue to run on fuel that also must be imported and paid for with forex.

In the 2018/19 fiscal year, Ethiopia spent about 360 million dollars on benzene. While this is lower than its import bill for other fuels needed for aircraft and construction vehicles, the nation is seeing passenger vehicle growth of 10pc a year, and benzene imports are growing fast.

In the last fiscal year, benzene was the only fuel to exceed targets set by the Ethiopian Petroleum Supply Enterprise. Though the Enterprise imported just 90pc of its target for gasoil, the biggest of its imported petroleum products, approximately 21.5 million additional litres of benzene had to be imported above its target to meet demand. At its current trajectory, Ethiopia may need to spend one billion dollars a year on benzene by 2030.

But all is not lost. By formulating new policies to increase the attractiveness of electric vehicles (EVs), Ethiopia could greatly diminish its future benzene import bills.

While your first impression may be that EVs are luxury vehicles only appropriate for Hollywood starlets and eco-conscious millionaires, much of the developing world is already awakening to the economic game changer they promise to become.

In India a new framework is being studied to completely end all sales of oil-fueled passenger vehicles by 2030 in order to reduce the country’s high demand for oil.

While EVs have coursed the roads of South Africa since 2014, in conjunction with the rollout of its I-PACE electric model earlier this year, Jaguar invested in 82 electric charging stations. More than 1,000 EVs have already been sold in the country.

BMW already has 30 charging stations across the continent and plans on investing in more stations through a partnership with Nissan. In Kigali, Rwanda a company called Ampersand has begun running trials with all-electric motorcycle taxis, which can reach speeds of 80Kph. In Mauritius the government has waived a 50pc excise tax on all EVs and hybrids and introduced new incentives for EV buyers.

And while EVs are still generally more expensive compared with similar oil-fueled vehicles, they already are at parity over the lifetime of the vehicle, with savings from fuel and reduced upkeep amounting to more than 1,000 dollars a year for most drivers. Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts that EVs will cost the same as oil-fueled passenger vehicles as soon as 2022 due to plunging costs in battery technology.

Ethiopia should focus on the long-term savings from EV vehicles. By introducing reduced import taxes on used EVs, the country can begin the experiment necessary to become a front-runner on the continent for the EV revolution. While this policy would have the government charge less in taxes at point of import, it would save upwards of 1,000 dollars a year per EV in benzene imports for many years to come. For instance, the 1.2 million EVs and hybrids on the road in the United States saved the country more than one billion litres of fuel in 2018 alone.

And policies should not end at imports. Peugeot, Lifan and Geely – three of the companies that already assemble vehicles in Ethiopia – already have EV models introduced in their home countries. With a little negotiation, foresight and pressure from the government, Ethiopia might not only have a burgeoning vehicle assembly industry in a decade but become the leading manufacturing hub on the continent.

PUBLISHED ON

Sep 07,2019 [ VOL

20 , NO

1010]

Editorial | Mar 11,2023

Life Matters | Apr 03,2021

View From Arada | Feb 16,2019

Radar | Feb 11,2023

View From Arada | Jul 24,2021

Photo Gallery | 96745 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 88928 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 67168 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65761 Views | Oct 02,2021

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 20 , 2024

In a departure from its traditionally opaque practices, the National Bank of Ethiopia...

Apr 13 , 2024

In the hushed corridors of the legislative house on Lorenzo Te'azaz Road (Arat Kilo)...

Apr 6 , 2024

In a rather unsettling turn of events, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (C...

Mar 30 , 2024

Ethiopian authorities find themselves at a crossroads in the shadow of a global econo...

Apr 20 , 2024

Ethiopia's economic reform negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are in their fourth round, taking place in Washington, D...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By BERSABEH GEBRE

An undercurrent of controversy surrounds the appointment of founding members of Amhara Bank after regulat...

An ambitious cooperative housing initiative designed to provide thousands with affordable homes is mired...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Ethiopia's juice manufacturers confront formidable economic challenges following the reclassification of...