Fortune News | Apr 06,2019

May 8 , 2021.

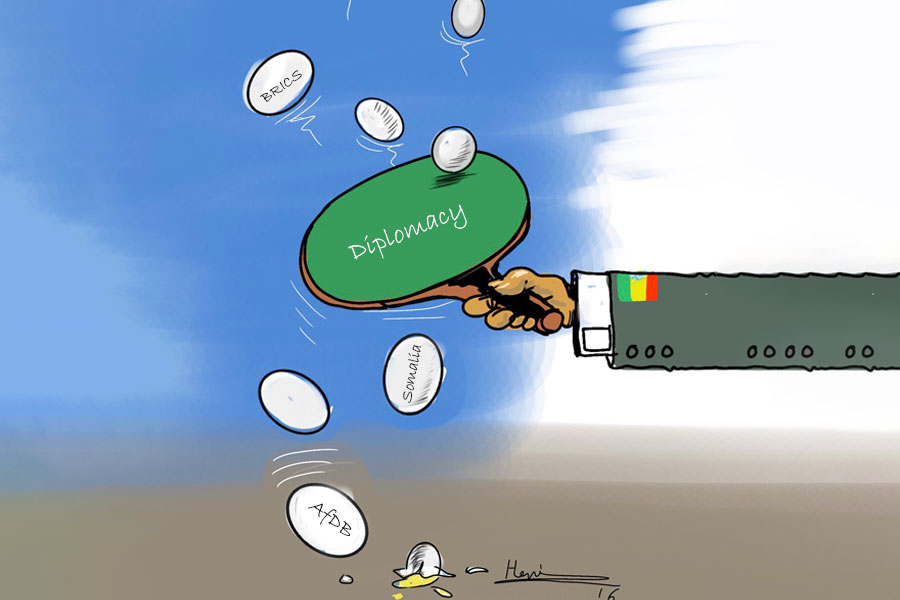

Diplomacy is not the forte of Ethiopia’s officials. They are often too absorbed in internal crisis or are mainly responding, instead of actively engaging, to threats, perceived or otherwise. Unfortunately, neither is it the specialty of any of the governments in the region. Without exception, each has disputes with one country or another threatening the breakout of armed conflict.

Perhaps most closest to this than any two countries at the moment are Sudan and Ethiopia. Go back a year, and the possibility of war may have sounded alarmist. Sure, they have come to stand on the opposite side of the dispute over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) over the years, especially since Omar al-Bashir’s ousting as president of Sudan.

But it was never that clear if Sudan even bought Egypt’s assertion that the GERD poses severe threats to the water security of downstream countries. To this day, in interviews, Sudanese Water Minister Yasir Abbas (Prof.) could be found forwarding that it offers a myriad of advantages to his country, from flood control to improving irrigation, albeit with the caveat that about 10pc of the issues that have not yet been agreed over pose a problem.

But how sharply and fatefully the days have changed.

Since November last year, Sudanese and Ethiopian forces continue to engage militarily over the disputed al-Fashqa area. The former’s rulers have taken to direly warning of the existential threat posed by the GERD to their country, asserting that it could be the cause of war. Ethiopian authorities, for their part, have come to accuse Khartoum of harbouring armed groups and carrying out joint training with Egyptian military forces. They have also taken to referring to Sudan as a tool whose national sovereignty has been sacrificed in the service of Egypt’s geopolitical interests. These had raised the stakes high and worsened diplomatic relations to lows not seen since the Dergueera when both were attempting to undermine one another actively.

The response to the deterioration of bilateral relations from Ethiopia’s side has been three-pronged: highlighting the advantages of the GERD to Sudan; restricting mediator roles to third parties except for the African Union; and, doubling down on its filling and operationalising schedule. By themselves, these goals would have advantages, at least where the rules of modern diplomacy apply. The countries have manageable disagreements that, in other regions, would have found a resolution through trusted inter-governmental institutions and the promise of building on previous binding agreements.

There is indeed no shortage of indicators that the threat of the Dam, at least to Sudan, is significantly limited. For instance, the GERD can boost Sudan’s aggregate GDP over decades by 47 billion to 83 billion dollars, according to a study supported by the Economic Research Forum.

Beyond this, the risks associated with the filling of the Dam have been argued to be perfectly within sight of the three countries.

This required “adaptations of Sudanese reservoir operations” to address water diversion risks to Sudan, as well as “agreed annual releases from the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a drought management policy for the High Aswan Dam, and a basin-wide cooperative agreement that protects the elevation of Lake Nasser.” The UK-funded study argued that a middle-ground exists if there is a will.

Unfortunately, neither the institutions nor a history of goodwill to accommodate such efforts exists in the region or between the three countries. The relationships between the governments are more often personalised and dictated on an assessment of temporary power balances than long-term national interests bound by strong institutions. The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and the African Union are too discredited and toothless to be considered with leverage over the management of such issues. Their failure to have abdicated moral and political leadership to the actions of national governments - sometimes without even so much as lip service - has degraded their relevance, if they ever had it.

Neither are inter-governmental agreements and settlements considered binding, which are kept in place only until one side or the other feels they could discard them. African governments, no less in Sudan and Ethiopia, are too unstable. Different leadership means such radical changes in the state's life that there is no accounting for what may come of agreements that have been signed with other countries.

A case in point is the border disputes between Ethiopia and Sudan. Since 1972, they had signed an agreement dictating that the status quo holdings of the territory of each country should be respected until an amicable solution is reached. In the early 2000s, a joint commission was formed to resolve the longstanding dispute. Even though it never finalised its mission, the border tensions boiled over earlier this year into armed conflict over the al-Fashqa area. It was a development that highlighted the lack of significance of talks, negotiations and joint committees to address disputes.

What is the point of civilian officials spending endless hours hammering out agreements if they could not be counted upon to keep their generals in check?

Compounding the issue is that, in the region, even the governments could not be trusted to respond based on their national interests. There are few countries in the world in a condition to risk plunging their people into state-on-state war.

Ethiopia and Sudan face extremely dire domestic political and economic crises, including armed conflicts, massacres and states of emergency. The last thing both could afford is national wars. But despite the hefty disadvantage of such a move, both governments feel that there is enough nationalistic sentiment and geopolitical rewards to reap to subject their people to further misery and deprivation.

As a result of a lack of respected regional institutions, suspect history of diplomatic relations and their own weak governments, neither Sudan nor Ethiopia have much maneuver room in the short term. Ethiopia can only go ahead with the filling of the Dam as it is too late to back down at the moment. Stalling it beyond the upcoming rainy season will add more delay with no promise of ever reaching an agreement. More importantly, as has been argued by experts such as Tirusew Asefa (PhD), chair of the Florida Water & Climate Alliance, construction of a central structure to the Dam means that “more water will be coming . . . during the summer rain that cannot get ‘unheld’.”

But this filling should be carried out with the promise on the Ethiopian side to reach a binding agreement with the two countries, which requires a compromise by all sides. Both Sudan and Egypt would need to recognise that they have been using shared resources to the exclusion of others. Any binding agreement can and should be tied with the caveat that Egypt agrees to incrementally reduce its water dependence on the Nile and invest in desalination and utilising its groundwater resources.

Addis Abeba would also need to give in on drought mitigation to address the understandable insecurity of Egypt. No doubt, Egypt’s, and by extension pro-Egypt Sudan’s, water shortage problem during times of drought cannot be put solely on the shoulders of Ethiopia. But a page could be taken out of agreements between the United States and Canada on flood control, where the three countries agree to share the risk of drought with Ethiopia, which will receive compensation for interrupted hydropower production.

Of course, this would require a basin-wide water allocation agreement and institutions to manage the three countries' interests. Making this nearly impossible is the distrust each country shares for the other, a nearly insurmountable challenge and the main reason where war between Sudan and Ethiopia cannot be ruled out.

This is where the international community could step in to reduce tensions. It could take a lesson from how the region was neglected until the circumstances of the most populous country deteriorated with the war in the Tigray Regional State back in November. All the signs were there for the reading but only came into focus once for the international community after it had started.

Global powers, including the United States, the European Union, China and Russia, as well as the United Nations, could take this wasted opportunity to bring to bear their influence over the three countries for a binding agreement. All the situation needs is pressure for leaders to turn back to their citizens and persuade them that compromise is necessary to avoid war.

PUBLISHED ON

May 08,2021 [ VOL

22 , NO

1097]

Fortune News | Apr 06,2019

Fortune News | Apr 22,2023

Radar | Nov 11,2023

Fortune News | Dec 17,2022

Fortune News | Jun 27,2020

Fortune News | Jun 29,2019

Commentaries | May 06,2023

Radar | Apr 24,2023

Fortune News | Mar 25,2023

Fortune News | Jul 18,2020

Photo Gallery | 96738 Views | May 06,2019

Photo Gallery | 88922 Views | Apr 26,2019

My Opinion | 67168 Views | Aug 14,2021

Commentaries | 65759 Views | Oct 02,2021

Feb 24 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

Abel Yeshitila, a real estate developer with a 12-year track record, finds himself unable to sell homes in his latest venture. Despite slash...

Feb 10 , 2024 . By MUNIR SHEMSU

In his last week's address to Parliament, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (PhD) painted a picture of an economy...

Jan 7 , 2024

In the realm of international finance and diplomacy, few cities hold the distinction that Addis Abeba doe...

Sep 30 , 2023 . By AKSAH ITALO

On a chilly morning outside Ke'Geberew Market, Yeshi Chane, a 35-year-old mother cradling her seven-month-old baby, stands amidst the throng...

Apr 20 , 2024

Ethiopia's economic reform negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are in their fourth round, taking place in Washington, D...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By BERSABEH GEBRE

An undercurrent of controversy surrounds the appointment of founding members of Amhara Bank after regulat...

An ambitious cooperative housing initiative designed to provide thousands with affordable homes is mired...

Apr 20 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Ethiopia's juice manufacturers confront formidable economic challenges following the reclassification of...